Why Chicago’s city treasurer is a waste of an elected office

Chicagoans vote for just three citywide officials. All of them should matter.

Chicago City Treasurer Melissa Conyears-Ervin made national headlines last week with her announcement that she would no longer invest the city’s cash in U.S. Treasury bonds––among the safest, most liquid investments on Earth.

No other American city has done this. And City Council members immediately questioned her decision.

Ald. Bill Conway was particularly incisive, noting that Conyears-Ervin’s 3.6% rate of return on the city’s $11 billion in cash last year underperformed the yield on 10-year Treasuries.

But Conyears-Ervin’s decision raises more fundamental questions.

What does Chicago’s treasurer do, exactly? And why is it elected?

The answers reveal how a hollow office wreaks havoc on the health of Chicago’s finances.

Chicago’s treasurer

The city’s current treasurer has made herself unusually vulnerable to criticism. Melissa Conyears-Ervin has been the subject of multiple ethics investigations and scandals since taking office in 2019.

Here are the toplines:

Security detail controversy: Conyears-Ervin briefly received a Chicago police security detail upon taking office. After a security assessment concluded neither the treasurer nor the city clerk required ongoing police protection, CPD withdrew that detail. Conyears-Ervin then hired private security guards using public funds. No previous Chicago treasurer is known to have received a CPD security detail. The controversy resurfaced in 2024 when Chicago Mayor Brandon Johnson attempted to bankroll the treasurer’s security team using the city’s water fund.

Asking banks for personal help: While overseeing deposits of city funds with BMO Harris and other banks, Conyears-Ervin acknowledged asking BMO to provide a loan to her husband’s landlord. Two former employees alleged she tried to “force” the bank to issue a mortgage on the building that houses the aldermanic office of Conyears-Ervin’s husband, 28th Ward Ald. Jason Ervin, who also serves as Johnson’s hand-picked chairman of the Budget Committee.

Repeated ethics violations: The Chicago Board of Ethics found in April 2024 that Conyears-Ervin committed 12 violations of the city’s Governmental Ethics Ordinance and moved to impose $60,000 in fines. In a separate probe, involving misuse of city resources and the firing of whistleblowers, she agreed to a $30,000 settlement to resolve those charges.

Whistleblower retaliation settlement: The city paid $100,000 to resolve a lawsuit brought by two employees who said they were fired after reporting misconduct inside the treasurer’s office. Their claims formed part of the basis for the Board of Ethics’ findings.

Political grandstanding: Conyears-Ervin is running for Congress, which helps explain the timing of her headline-grabbing U.S. Treasury announcement.

As is so often the case in Chicago, the problem here is not merely the office-holder.1

The much bigger problem is the office itself.

The mayor, the clerk, and the treasurer

Per state law, Chicago voters elect three citywide officials.

First is the mayor. No big-city mayor is granted more authority than Chicago’s. And in comparison, the other two citywide offices are meaningless.

One is the clerk, who is elected citywide but has almost no policy authority. The office mainly administers records and vehicle stickers. It is clerical in the most literal sense.

The other is the treasurer, who is responsible for managing the city’s cash and investments in a purely custodial role. The office:

Cannot direct budgeting

Cannot influence debt issuance

Cannot audit spending or enforce fiscal discipline

Cannot order contributions to the city’s pension systems

Sits on pension boards but wields no binding authority

The city treasurer’s office does not function like a comptroller, CFO, or financial watchdog.

It functions like a politically active bank teller with a press team.

A better office

Other major cities have independently elected controllers, comptrollers, or chief financial officers—and these offices actually mean something:

The New York City Comptroller audits every agency, reviews every contract for fiscal compliance, and manages the five city pension funds as a fiduciary.

The Los Angeles City Controller has the power to conduct performance audits of all departments and city programs, with few exceptions.

The Houston City Controller serves as the city’s chief financial officer, independently certifies the availability of funds for the budget, and is responsible for oversight of the city’s debt and investment portfolios (including reviewing debt issuances).

Chicago’s treasurer has none of the oversight, audit, or fiscal-control powers that these offices have in other major cities.

Here, our treasurer’s responsibilities are laid out in city code. And City Council could change those responsibilities.

In every other major city, this office’s responsibilities are contained in their voter-approved city charters.

No fiscal oversight

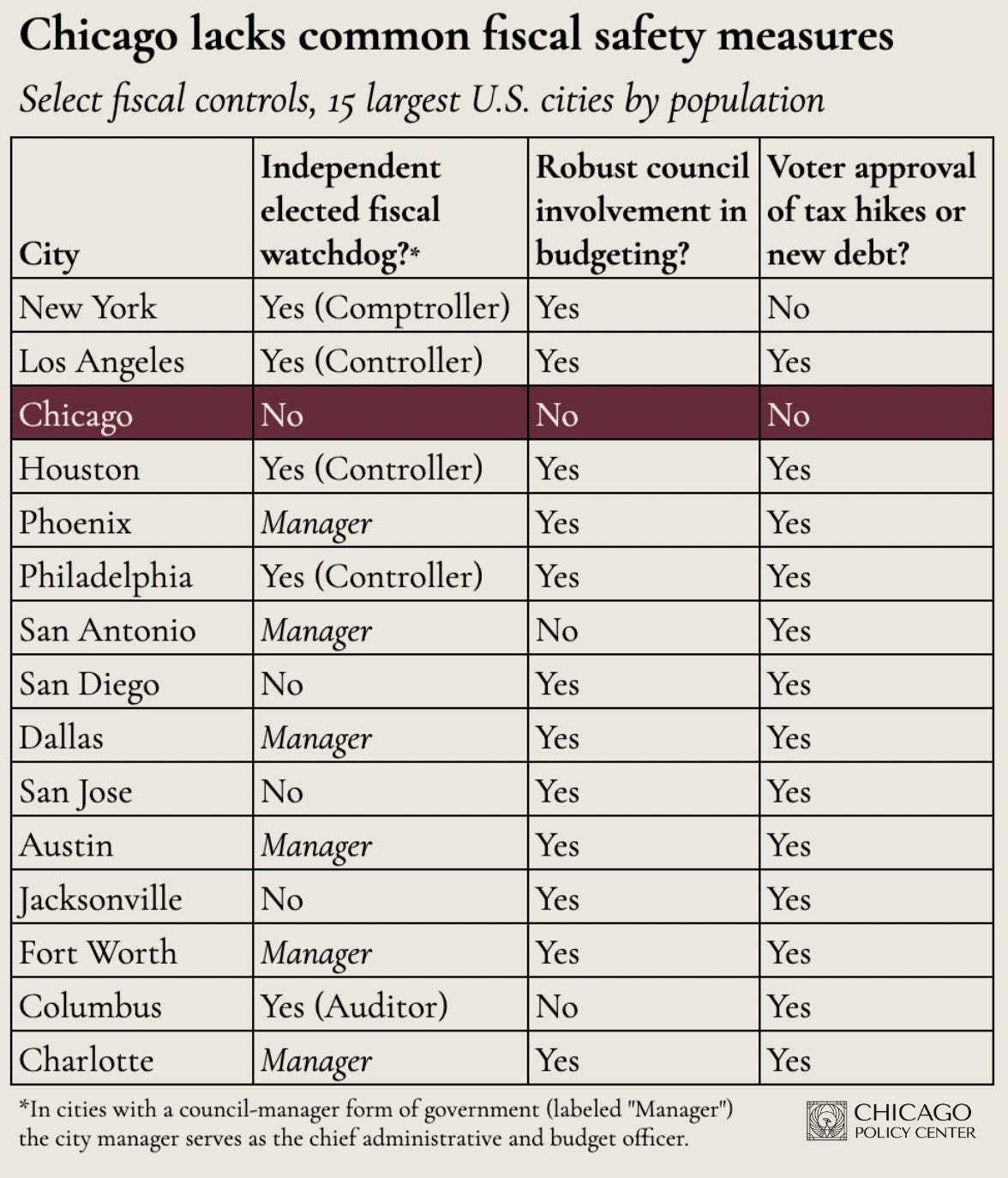

Big cities commonly have at least one of the following three fiscal controls that prevent reckless budgeting:

An independently elected controller, CFO, or auditor

Voter approval of tax hikes or new debt

Robust city council involvement in the budgeting process

Chicago is the only major city in the country that lacks all three.

By reforming the treasurer’s office to become a real fiscal player on par with the mayor and the council, Chicago could put in place a critical safeguard for city residents.

Until that happens, expect more political stunts and underperformance.

In the news

I joined Christopher Sweat at GrayStak Media for an hourlong interview on Chicago’s political history and the current budget fight. GrayStak is the only outlet providing consistent, in-depth, live coverage of Chicago protests, which is how Chris’ team captured the now-famous footage of Border Patrol agents chasing a man on his e-bike down Dearborn Street. I enjoyed our conversation.

I also joined the Mincing Rascals podcast on WGN Radio to discuss Gregory Bovino leaving Chicago and the end of the federal government shutdown. My “green light” recommendation: Andrei Tarkovsky’s “Mirror” (1975), which Siskel Film Center is screening Nov. 11 and Nov. 17.

The most notable and interesting Chicago city treasurers all served long before the current form of the office was established, including:

George W. Dole (Treasurer from 1839-1840): Ran the first grocery store in Chicago, built the first grain storage facility and the first slaughterhouse in Chicago, helped organize the Chicago Board of Trade, was director of the first state bank of Illinois, served as Chicago’s customs inspector, and was appointed the 7th postmaster of Chicago by President Millard Fillmore.

Amos Throop (1865-1867): A businessman and staunch abolitionist who founded Throop University in Pasadena, California in 1899. Thirty years later, administrators gave Throop University its current name: the California Institute of Technology.

Charles Gunther (1901-1903): A German-American candy empresario whose collection of historical objects included the table on which Robert E. Lee signed the terms of surrender that ended the Civil War. When Gunther’s collection outgrew his candy emporium, he created a Civil War museum by purchasing a Confederate prisoner-of-war camp in Richmond, Virginia, called Libby Prison. He dismantled the building, shipped it to Chicago on 132 railroad cars, and rebuilt it on Wabash Avenue. The Libby Prison War Museum opened in 1889. Much of Gunther’s collection is now housed at the Chicago History Museum.