Why you can’t start a Chicago-style hot dog cart in Chicago

An unworkable licensing regime is hurting the city's culinary culture.

In Los Angeles, bacon-wrapped hot dogs are a street food staple.

New York City’s “hot dog king” Dan Rossi runs a legendary stand outside the Met.

And an IRS attorney on furlough went viral last fall for starting his dream hot dog cart in Washington D.C.

But in the home of Chicago-style hot dogs, there is not a single food-cart vendor licensed to sell hot dogs on a city sidewalk, according to a Chicago Policy Center review of city data.1

No matter one’s culinary talent or work ethic, city regulations make hot dogs—and other street-food staples—effectively illegal to sell from a cart.

With tamale vendors facing unprecedented crackdowns from federal agents, a weak city job market, and candidates for mayor and City Council preparing for municipal election season, is it finally time for the city to stop criminalizing street food?

Food fight

For decades, Chicago was one of only two cities in the top 25 by population that did not allow food-cart street vending at all.2

Risk-averse city officials and lobbyists for brick-and-mortar restaurants worked together to keep it that way.

But in 2015, I was fortunate to work on what remains the largest-ever survey of Chicago food-cart vendors, and met inspiring women like Claudia, Cecilia, and Joaquina who woke before dawn each day to prepare tamales and sell them on the street to support their families.

Survey data from nearly 200 of the estimated 1,500 food-cart street vendors across Chicago found an industry generating an estimated $35.2 million in annual sales, $16.7 million in annual income, 2,100 jobs, and 50,000 meals a day—supporting 5,000 dependents.

But it was all underground.

Vendors risked daily harassment from criminals and law enforcement alike.

So I was proud to stand with those women and their families at City Hall on Sept. 24, 2015, when City Council passed an ordinance creating the first modern license for food-cart vendors in Chicago.

A year later, I profiled the recipients of the first licenses for tamale carts: Abraham and Maria Celio, owners of Yolis Tamales in Back of the Yards.

“We feel a lot of pride, a lot of happiness,” Maria said. “And we feel more secure and confident in selling our food. We aren’t working with the fear of being fined.”

But nearly a decade later, the Celios are among just three licensed tamale cart vendors in a city of 2.7 million people. In fact, their family is one of only 12 licensed food-cart vendors of any kind in Chicago.

“I feel happy for my father, who doesn’t have to worry about police anymore,” Abraham said.

“But at the same time, I feel sad for people who still struggle and have not been able to get the license.”

So what went wrong?

Unreasonable rules

The 2015 ordinance created a new license for food-cart vendors called the Mobile Prepared Food Vendor license.

But in its design, the city shut out virtually all food-cart vendors that Chicagoans see on the street today.

Critically, the license does not allow for food handling of any kind on a cart.

A key provision notes that “food may not be prepared on or in” a food cart. And the city interprets “preparing” food to mean an action as small as placing a hot dog on a bun.

That’s one reason Chicagoans don’t see Chicago-style hot dog carts.

Even dispensing coffee from an urn counts as “preparing” and thus cannot happen on a cart. This prevents scores of champurrado vendors across the city from getting a license, for example.

City rules also don’t allow for carts with a propane tank, which bans vendors from using slick new carts like The Tamalero, which is legal in Los Angeles. This is another hurdle for tamale vendors and hot dog vendors alike.

Abraham and Maria Celio were able to pour thousands of dollars into designing and fabricating their custom tamale carts with direct input from city regulators—and critically, can prepare their tamales in the licensed commercial kitchen in their own brick-and-mortar restaurant—but they are the exception.3

Chicago’s tamale vendors are daunted by the paperwork, the process, and the overly restrictive rules.

So they remain unlicensed.

New York City expanding

New York City, already home to 7,000 licensed mobile food vendors, will add an additional 2,200 mobile food vendor licenses each year for the next five years under a bill passed by City Council in December.

Newly elected Mayor Zohran Mamdani is expected to sign it.

Indeed, Mamdani built early momentum in his historic campaign by championing the city’s street vendors, noting red tape was driving “halal-flation.”

Regardless of their feelings on other elements on Mamdani’s agenda, enterprising candidates for Chicago mayor and City Council in 2027 would be wise to take on the same underdog fight on behalf of Chicago’s street vendors.

Unseen costs

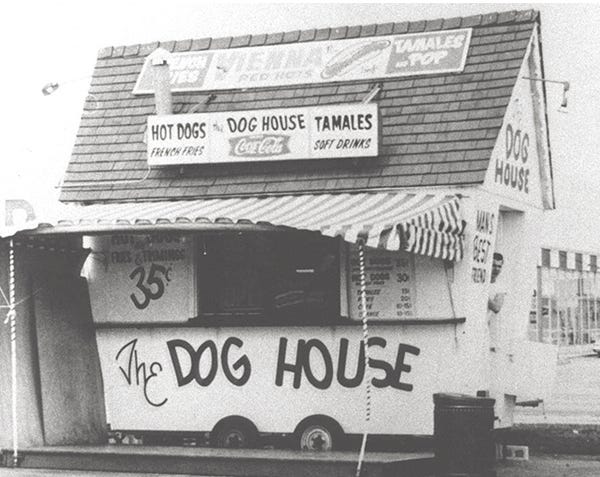

In 1963, a 23-year-old returning from the Marines purchased a 6’ by 12’ trailer for $1,100 to start The Dog House in Villa Park.

The trailer had no bathroom and relied on running 250 feet of garden hose from a nearby building for running water.

That man was Dick Portillo.

In 1893, Austrian-Hungarian immigrants Emil Reichel and Sam Ladany introduced their all-beef sausages at the World’s Fair. The success of their small hot dog stand at the Austrian Village exhibit led to their first storefront a year later.

That business would go on to become Vienna Beef—the foundation of the Chicago-syle hot dog.

These stories show how today’s food-cart regulations are killing tomorrow’s titans of Chicago’s culinary community.

City leaders ought to change them.

Buying a Chicago-style hotdog from a cart requires hiring a speciality catering service or finding one of a handful of seasonal vendors selling hot dogs on Chicago Park District land. Park District concessions are subject to different regulations.

Note that food carts are not the same as food trucks, which also face overly restrictive regulations from City Hall.

Another difficulty in licensing tamale carts is that nearly all vendors prepare their food in their home kitchens, while the license requires all food preparation take place in a licensed commercial kitchen.

I was just thinking about this fact the other day and how annoying it is that Chicago doesn't have more food carts and/or food trucks or pods around the city. One of the best tacos I've ever had was in LA from a food truck located in a gas station parking lot off a highway. How do folks help make change around this? It's been 10 years since the law was passed and it's time for politicians and the city to revisit it?