Harvey tips the first domino in Illinois’ municipal debt crisis

While cameras focused on Chicago Mayor Brandon Johnson’s budget speech last week, a quieter but more consequential story unfolded just 25 miles south of City Hall.

Harvey, Illinois, a city long drowning in debt, made history. Its city government became only the second in 35 years to seek state oversight under Illinois’ Financially Distressed City Law.

What happens next matters not only for Harvey, but for Chicago and the rest of the state.

Let’s get into it.

Distressed city

Harvey is a textbook case of how government debt can hollow out a once-prosperous community. Decades of corruption made things worse. But pension problems are at the heart of Harvey’s crisis.

Consider:

The firefighter pension fund has just 18 cents for every dollar it needs to pay its liabilities, which total $58 million.

Illinois already confiscates 35% of Harvey’s state-collected tax revenue and diverts it to pensions.

The city has laid off about half its public safety workforce in recent years, in order to afford debt payments.

In part due to court-ordered property tax hikes to pay its bills, Harvey has some of the highest property tax rates in the country, an eye-watering 4.7% for residential and 17% for commercial property.

Harvey can only collect half of what it levies in property taxes, according to the Civic Federation, because so many residents can’t shoulder the burden.

Last week, Harvey’s city council voted unanimously to certify Harvey as a “distressed” city under Illinois law. That designation allows the state to create a Financial Advisory Authority—a body that can approve budgets, loans, and contracts and oversee the city’s finances.

But the authority can’t rewrite existing contracts, restructure debt, or touch pensions. In other words: it can’t fix what’s fundamentally broken.

A case in point is the only other city in Illinois history to file for oversight under this law: East St. Louis. It remained under state oversight for 23 years. But that oversight never solved the underlying problem. Families and businesses in East St. Louis remain stuck in financial purgatory today, with the city reporting just $3.3 million on hand for its firefighter pension fund against $78 million in liabilities—a funded ratio of just 4%.

Harvey’s path today looks alarmingly similar. Without deeper reform at the state level, any “oversight” will amount to little more than managed decline.

Harvey isn’t alone

It’s not just Harvey. A similar story is playing out across Chicago’s south suburbs, where pension costs are crowding out core services, jacking up property tax bills, and eroding home equity.

Take Matteson, where homeowners like Patricia Hill are getting pummeled. She bought her house in 2003 for $315,000. Two decades later the value had dropped to $215,000, with a $10,000 property tax bill.

“This is supposed to be the American Dream for me and my family,” Hill told me in 2020. “I’m holding on to everything I can, but I’m losing because of this house. It’s a nightmare.”

While homeowners like Hill are living in a nightmare, retired south suburban school superintendents are living in luxury. Take former Calumet City school district superintendent Troy Paraday. His pension is rich enough to buy a house like Hill’s every year in perpetuity. And still have plenty left over.

Paraday was the highest-paid school district administrator in the state with a salary over $430,000. He was fired after an investigation into numerous allegations of misconduct, including deceiving the school board on financial matters relating to his compensation, claiming the board gave him a 6% raise when it had not and accumulating compensatory time which his contract did not allow for.

The school board alleged Paraday allowed himself to accumulate unlimited compensatory time for work beyond an eight-hour day, logging phony time for duties considered part of his job such as conducting interviews, attending board meetings, conferences, graduations and collective bargaining negotiations. This led him to seek a payout of more than $1.75 million for 885 sick, vacation and personal days he “saved” while working for the district. His scheme helped inflate his pension payment, which currently stands at $25,265 per month, to over $300,000 annually.

This isn’t fair. And it’s not sustainable.

A way out

Illinois cities like Harvey are trapped. They’re blocked by the state constitution from adjusting pensions they can’t afford. And they’re barred by law from filing Chapter 9 municipal bankruptcy.

Chapter 9 is a last-resort tool. It’s a way for insolvent governments to restructure debt, renegotiate obligations, and protect essential services for residents. But unlike 24 other states, including California and New York, Illinois doesn’t allow for it.

Chicago’s south suburbs are primed for revival. They have what most regions would kill for: infrastructure, proximity to the city, transportation networks, and abundant, affordable land. These communities just need appropriate tools to right the ship. Chapter 9 is one of those tools.1

Lessons for Chicago

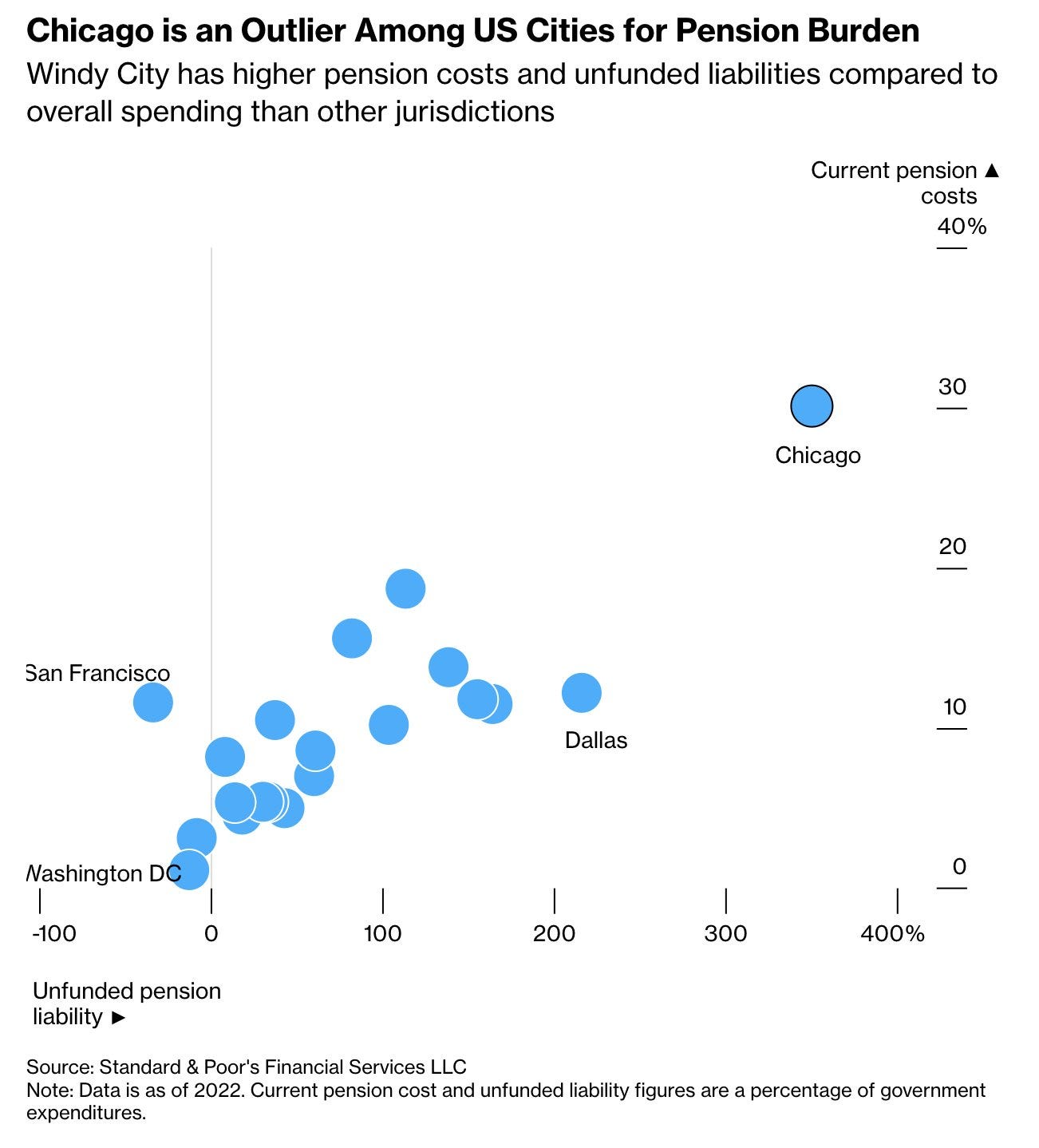

Chicago’s tax base is much more robust than Harvey’s. Or any south suburb for that matter. But it too is on an unsustainable path. And it lacks the tools to unshackle residents from a crushing debt burden.

The city’s annual budget crises are fueled by unsustainable pension costs. Just take a look at pension payments out of the corporate fund over the last decade.

In the short-term, Chicago should pass a balanced budget without tax hikes. You can read the Chicago Policy Center’s Chicago Forward plan here, which does just that. We were also first to report the details of Chicago Mayor Brandon Johnson’s ill-advised tax hike proposals last week (see here and here).

But in the long term, Chicago also needs the option of Chapter 9 bankruptcy protection. Not necessarily to file for Chapter 9 immediately, but as a tool to bring all parties to the table for serious negotiation. And if those negotiations fail, the acute resolution that Chapter 9 can bring to the city is far better than a chronic, unresolved default.

Illinois must give its cities a way out. Before the next domino falls.

In the news

Thanks to all those who came to the sold-out Mincing Rascals taping in Ottawa, Illinois, on Friday.

I did not fully appreciate the extent to which John Williams is the king of that town.

That live episode should be published soon. In the meantime, you can listen to Wednesday’s episode here. My “green light” recommendations: One Battle After Another (2025) and D’Angelo’s Voodoo (2000).

A special thanks to all who reached out in response to last week’s edition of The Last Ward on Operation Midway Blitz. Sadly, the belligerence continues.

State Sen. Kimberley Lightford, D-Maywood, filed a bill allowing for municipal bankruptcy protection in 2017.