One year later: What the gift room scandal reveals about Chicago

The city's governance structure actively works against accountability.

It’s been one year since Chicago Inspector General Deborah Witzburg dropped a bombshell report revealing Mayor Brandon Johnson’s office had accepted hundreds of gifts—including Hugo Boss cufflinks, Gucci handbags and premium whiskey—without properly reporting them as required by the city’s ethics ordinance.

The headlines were, predictably, spectacular.

Designer handbags! A mystery gift room! The mayor blocking investigators from entering!

And that’s exactly the problem.

Welcome to what I’ve dubbed “Gift Room Syndrome“—when a dramatic scandal is so theatrically absurd that Chicagoans miss the deeper, more troubling lesson hiding in plain sight.

As I wrote when this first broke, the infamous gift room scandal was never really about Brandon Johnson hoarding luxury goods for his personal benefit.

The real scandal—the one that should concern anyone who cares about Chicago’s future—is what the scandal revealed about how our city government is structured.

What actually happened

Here’s the gift room story most Chicagoans know: The mayor accepted fancy gifts. The Inspector General tried to investigate. The mayor’s office blocked access to a “gift room” where the items were supposedly stored. Eventually, Johnson released a 22-second video showing shelves of mostly unremarkable trinkets.

Here’s what many people don’t know: The gift room didn’t even exist when investigators first tried to inspect it.

In November 2025, Witzburg revealed the closet-sized room Johnson’s office eventually showed to the press wasn’t constructed until February 2025—after she first attempted an unannounced inspection.

Let that sink in. When the IG first tried to see where gifts were stored, there was no gift room. City lawyers blocked her from entering. Then the mayor’s office built one and acted like it had been there all along.

As Witzburg put it: “We or anybody else has no way of knowing, in an independent, confirmed way, what exactly was happening with that city property before the new gift room was built.”

The mayor’s office blocked the IG’s access not once, but twice. The second attempt, involved investigators trying to inspect a city office where they believed gifts were improperly stored. Again, Corporation Counsel lawyers intervened to prevent the inspection.

And those public tours Johnson promised? According to the mayor’s spokesperson, exactly two people signed up. Neither showed up.

What the gifts revealed

The gift room fiasco exposed a systemic breakdown in oversight and accountability—a pattern that Witzburg called the mayor’s “hostility to oversight.”

But it’s deeper than that.

Consider what actually happened: For decades preceding the Johnson administration, when it came to recording and storing gifts to the city, Chicago mayors operated under an “unwritten arrangement” with the Board of Ethics that allowed them to completely ignore the city’s own Government Ethics Ordinance.

That ordinance required prior approval of many gifts, reporting to the Board of Ethics and reporting to the city comptroller. But Chicago mayors ignored all of that. Instead, they kept a logbook somewhere on the fifth floor that the public could theoretically request to see.

When the IG tried to verify that this “public” log was actually accessible, mayoral staff denied the request and told them to file a FOIA instead. Then the mayor’s office simply ignored the FOIA.

Only when the IG issued a formal investigative request did the administration produce the log—revealing hundreds of undocumented gifts, many from unknown donors.

Then, when investigators tried to physically inspect where these gifts were stored, the city’s Corporation Counsel stepped in to block them.

The pattern shows deliberate obstruction of the city’s own watchdog.

A pattern of obstruction

The gift room fits into a broader pattern of the Johnson administration’s approach to oversight. In February 2025, the Inspector General issued a memo accusing the Law Department of “selectively” opposing OIG investigations when they “may result in embarrassment or political consequences to city leaders.”

The memo detailed how Corporation Counsel has:

Withheld city documents based on dubious attorney-client privilege claims

Demanded to sit in on OIG investigative interviews

Delayed enforcement of OIG subpoenas

This is the same Law Department that, under previous leadership, fought to withhold the Laquan McDonald video until a court ordered its release. The same department that in the gift room case was, as the IG’s report put it, “apparently representing the mayor in opposition to the OIG.”

That phrase—”representing the mayor in opposition to the OIG”—gets to the heart of Chicago’s governance problem here. The Law Department is supposed to represent the city and the public interest. Instead, it operates as the mayor’s personal defense firm.

As I detailed in April, Johnson has not led the passage of a single piece of anti-corruption legislation during his time as mayor—until the gift room scandal forced his hand. He actively blocked other elected officials’ efforts, from killing an ordinance restricting lobbyists’ political giving to refusing to recuse himself from negotiations with his former employer and largest campaign contributor, the Chicago Teachers Union.

Gift Room Syndrome in action

This is where Gift Room Syndrome kicks in. The more dramatic the story—designer handbags! hidden closets! mystery donors!—the less likely residents grasp the most important lesson.

Chicago saw this play out with the recent investigation into how the public learned about the Chicago school board’s plan to hike property taxes over the Christmas holiday. The headline was Onion-esque: Mayor uses property taxes to investigate how residents learned of higher property taxes.

But the real scandal wasn’t the investigation into the “leak.” It was that Chicagoans should have been voting on an extra $550 million in property tax revenue flowing to CPS this year—but never got that vote, thanks to the TIF loophole that allows the city to subvert the state’s property tax cap.

It’s the same dynamic: A dramatic surface story obscures deeper systemic failure.

Why obstruction of oversight matters

Chicago faces serious challenges that will require a combination of cutting some spending, slowing the growth of other spending, and raising new revenue of some kind—whether for schools, infrastructure, or basic services.

But raising new revenue requires public trust. And public trust requires accountability.

This is one reason Johnson’s “Bring Chicago Home” referendum failed. Voters rejected the real estate transfer tax increase in large part because the administration wasn’t transparent about how the money would be spent. When government actively blocks oversight, it poisons the well for any future ask.

As Inspector General Witzburg said: “My fear is that what we are seeing here is less about the cuff links and the size 14 men’s shoes, and it’s more about hostility to oversight.”

When the mayor’s office can ignore ethics ordinances through “unwritten arrangements,” block the Inspector General from doing her job, deploy city lawyers to protect political interests over public accountability, and face zero consequences—the system is designed to avoid scrutiny rather than enable it.

The structural problem

Here’s what the gift room scandal revealed: Chicago lacks the basic structural safeguards that prevent this kind of dysfunction in other major cities.

The Corporation Counsel is appointed by the mayor and serves at the mayor’s pleasure. When the IG tries to investigate the mayor’s office, the mayor’s own lawyers block the investigation. This is by design.

Other big cities have a different approach:

In Los Angeles, Columbus, and San Francisco, the city attorney is elected independently.

In San Antonio and Austin, the city attorney is appointed by and reports to a city manager who is accountable to the city council.

In San Jose, the city attorney is appointed by and reports directly to the city council.

Chicago also lacks meaningful protections for its Inspector General. When Witzburg tried to inspect city premises—as she is explicitly authorized to do under city ordinance—the Law Department simply said no.

To her credit, Witzburg fought back. In February 2025, she asked the City Council to pass protections preventing this kind of interference. Ald. Matt Martin introduced an ordinance to do that.

After months of negotiations, the ordinance passed in July 2025. The final version was a compromise—it restricts when Law Department lawyers can attend investigative interviews and limits improper attorney-client privilege claims, though it removed provisions on subpoena enforcement that Witzburg had sought.

Still, as Witzburg said after passage, the ordinance represents “a tremendous step toward aligning Chicago with national standards and federal law on independent oversight.” It took the gift room scandal, public pressure, and Witzburg’s willingness to fight, but the reform happened.

This raises a question: Does one hard-won ordinance, passed only after intense public scrutiny of the gift room debacle, fundamentally change the structural problems here?

What reform actually looks like

If Chicago is serious about preventing future gift room scandals—and the deeper accountability failures they represent—the city needs structural reforms:

1. Strengthen OIG protections further

The ordinance passed in July 2025 was a good start, but it was a compromise. The final version removed provisions on subpoena enforcement that the IG had sought. Chicago should continue building on this progress to ensure the watchdog has full enforcement power without Law Department interference.

2. Elect the Corporation Counsel, or take it out of the mayor’s office

An independently elected city attorney would owe their loyalty to voters, not the mayor. They could provide actual oversight instead of political protection. This is how Los Angeles, Columbus, San Diego and San Francisco operate. Short of making the corporation counsel an elected position, the role could report to a city administrator—a position that is actually supposed to exist in Chicago. As Ed Bachrach and I noted in 2021, Chicago’s Municipal Code requires the mayor to appoint an administrative officer (essentially a city manager) who must be confirmed by the City Council. This position, created in 1954, is designed to “supervise the administrative management of all city departments” and provide coordination across agencies. But no mayor has bothered filling it since Jane Byrne. Reviving this long-dormant position—and having the corporation counsel report to it rather than directly to the mayor—would help create the independence necessary for real oversight.

3. Create enforcement mechanisms through a city charter

The gift room scandal revealed that Chicago’s ethics ordinance was effectively optional. Decades-long “unwritten arrangements” allowed officials to simply ignore requirements.

Chicago should follow other big cities’ practices of establishing a city charter with regular charter revisions—empowering civic leaders to thoroughly review and update governance structures that can’t be waived through backroom deals.

A proper city charter, approved by voters, could create real accountability through:

Clear procedures for ethics compliance that can’t be waived by informal agreements

Independent ethics enforcement with real penalties

Legal standing for citizens to sue the city into compliance when officials violate charter provisions

4. Consolidate inspector general offices

Chicago has five different IGs (city, CPS, CHA, Park District, City Colleges) with wildly different powers and funding. Consolidate them under one roof, like New York’s Department of Investigation, with consistent authority and resources.

5. Overhaul the Board of Ethics

The current board enabled the “unwritten arrangement” that allowed gift room syndrome to fester for decades. Chicago should follow New York’s model of a Conflict of Interest Board with real training, enforcement, and investigative capacity.

One year later

It’s been 12 months since Chicago learned about the gift room. The mayor’s office has released new guidelines. There’s an online gift log now. And you can sign up for a tour.

But the fundamental problem remains: Chicago’s governance structure actively works against accountability. The mayor controls too much. Independent oversight is too weak. And when watchdogs try to do their jobs, the mayor’s own lawyers stop them.

Gift Room Syndrome strikes when we let the dramatic details distract us from that reality.

The question one year later isn’t whether Johnson will accept more questionable gifts. The question is whether Chicago will finally build a government where oversight works regardless of who sits in the mayor’s office.

Until the city addresses that structural failure, Chicago will keep stumbling from scandal to scandal, outrage to outrage, always focused on the symptoms while the disease spreads.

Chicago deserves better than government by “unwritten arrangement.” We deserve a charter that can’t be ignored, watchdogs that can’t be blocked, and accountability that doesn’t depend on the mayor’s good graces.

The gift room’s first anniversary is as good a time as any to demand it.

In the news

Early voting across Illinois begins soon for the March 17 primary elections.

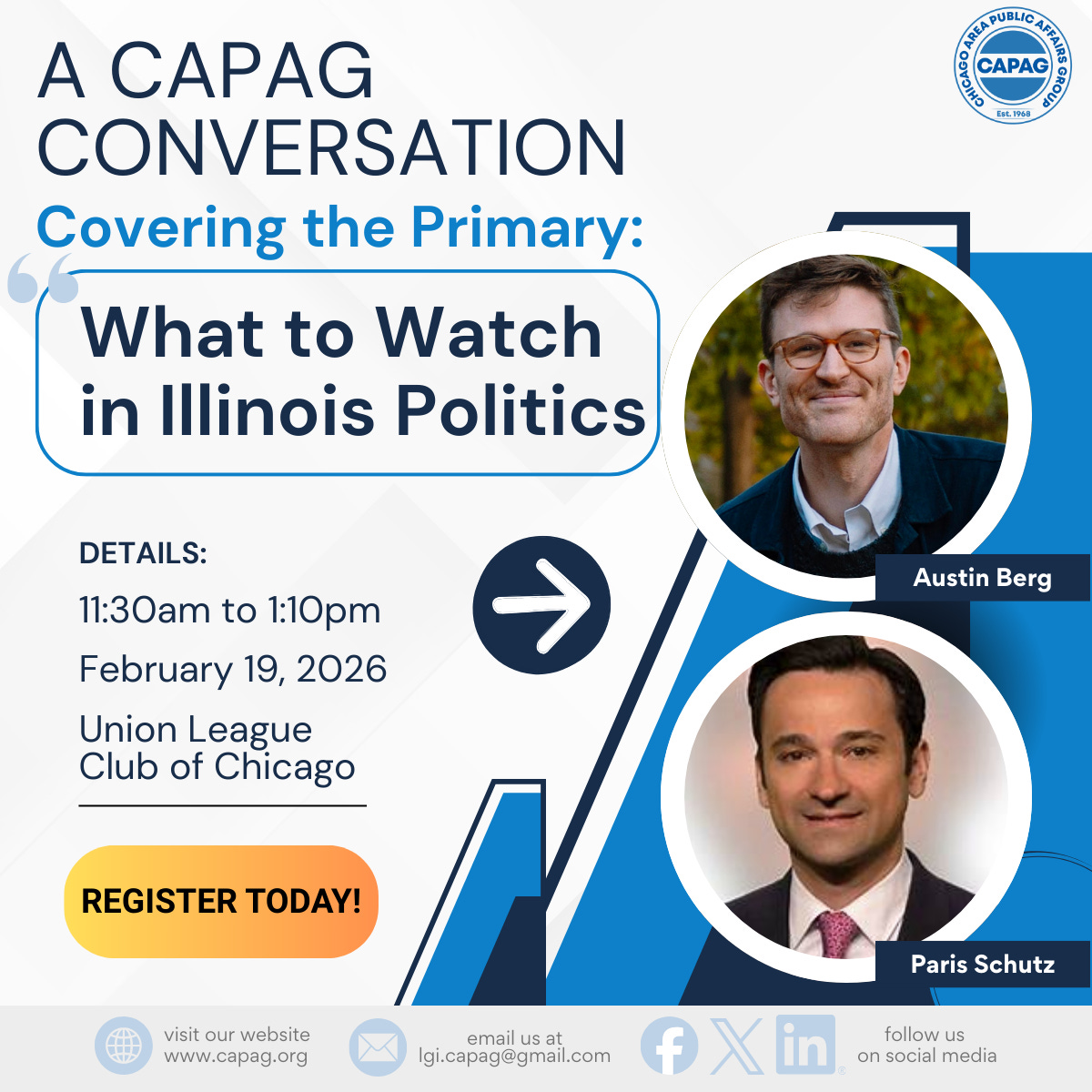

For a deeper discussion on those elections, I’ll be joining the Chicago Area Public Affairs Group at the Union League Club on Feb. 19.

Members of the general public can buy tickets here.

There are eight million stories in the Naked City...this has been one of them.