The truth about TIFs: Chicago’s secret property tax hikes

How financial shell games and a loophole in state law denies Chicagoans the power to vote on their property tax bills.

Chicago has just over two weeks left to pass a city budget. The clock is ticking.

Much of the budget drama has centered around Mayor Brandon Johnson’s demand for a controversial “head tax,” which would bring in an estimated $82 million.1

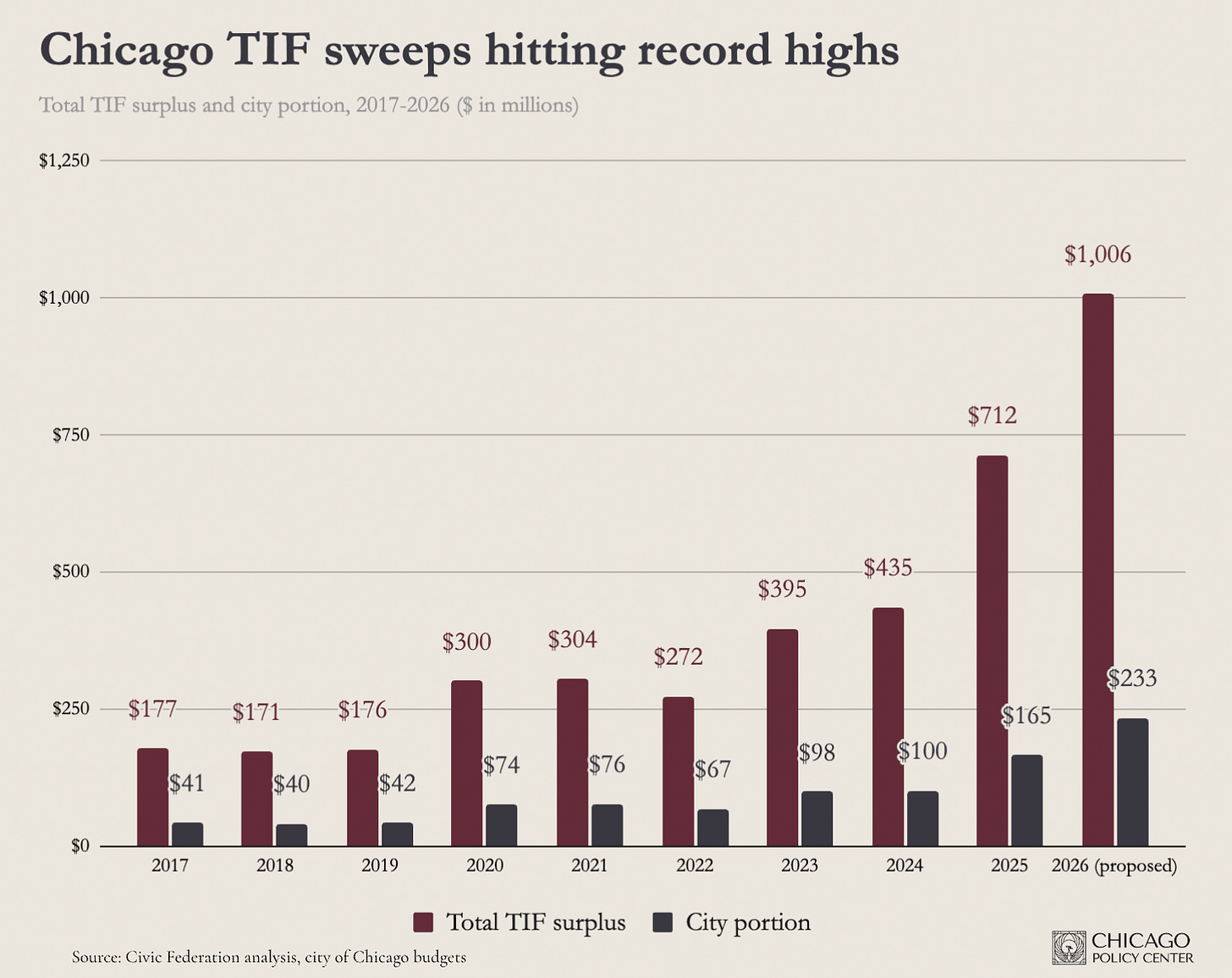

But far less attention has been paid to a move with a far greater impact on the budget: the mayor’s proposed $1 billion sweep of Tax Increment Financing districts, or TIFs.

It is impossible to understand the current budget battle—and the record-breaking property tax increases that just hit Chicago homeowners—without first understanding TIFs.

In this week’s edition of The Last Ward, we dive into a critically important part of the budget process that most voters don’t understand. And how political leaders are taking advantage of that ignorance to pass back-door property tax hikes, costing homeowners thousands of dollars a year.

What are TIFs?

In theory, TIFs are supposed to be economic development tools.

In practice, TIFs have become a core feature of Chicago’s operating budget, one of many poorly governed elements in the city’s budgeting process.

Here’s how TIFs are supposed to work:

The mayor signs an ordinance, passed by City Council, creating a TIF district in a “blighted” area of the city.

Within a TIF district, property values grow, which means higher property tax collections.

Those incrementally higher property tax collections are skimmed off into a TIF fund every year. Meanwhile, the frozen “base” of property tax collections in the district continue flowing to the city, the schools, the parks and other local governments. Each TIF district lasts 23 years.2

The city uses the TIF funds for projects inside the TIF district, or nearby, to eliminate blight and spur redevelopment.

But here’s how TIFs actually work in Chicago:

The city is blanketed with 108 TIF districts, including downtown areas like LaSalle Street that could hardly be described as “blighted.”

TIFs captured a record 42% of the city’s property tax revenue in 2023. This is an extraordinary share unmatched by any other major U.S. city.

Some TIF dollars fund economic development. The Chicago Riverwalk is a prominent example of a worthy, TIF-funded project. The Wintrust Arena is a prominent example of a dubious one.

Increasingly, TIF functions as a shadow budget for the city and Chicago Public Schools. Instead of being spent on redevelopment, funds are routinely swept as part of the city’s budgeting process and used to plug operating deficits. As we’ll see, this practice allows CPS to boost its property tax collections without seeking approval from voters.

To get a sense of Chicago’s unprecedented reliance on TIFs to plug budget holes, here’s the declared TIF surplus each year since 2017, and the share of that surplus flowing into the city’s operating budget.

That brings us to the current budget fight, which is expected to come to a head during a string of City Council meetings this week.

The TIF shell game

Mayor Brandon Johnson is proposing a record $1.01 billion TIF sweep to help fund the city’s operating budget. But it’s not just the city. Per state law, any TIF “surplus” must be distributed proportionally to local governments.

That’s where the shell game begins. Here’s how it works:

The entity getting the largest chunk of Johnson’s proposed TIF sweep by far is Chicago Public Schools, which would receive $550 million.

But the current CPS budget only relies on $379 million from TIFs. The alternate budget supported by a majority of City Council members proposes a smaller TIF sweep—enough to generate that $379 million for CPS.

Johnson is pushing the higher, $1 billion sweep so CPS can then turn around and make a $175 million pension payment back to the city. This is exemplary of the shell games at play with TIF, which ultimately moves money in circles, obscuring who is taxing whom—and why.

It’s easy to see how TIFs fly in the face of their stated purpose. And how they allow for shell games with budgeting.

But the more important (and perhaps least understood) element of TIFs is how they trigger higher property tax bills.

TIFs cause property tax hikes without a vote

Typical Chicago homeowners saw their property tax bills jump 17% this year, according to the Cook County Treasurer’s Office. That’s the largest increase in 30 years.

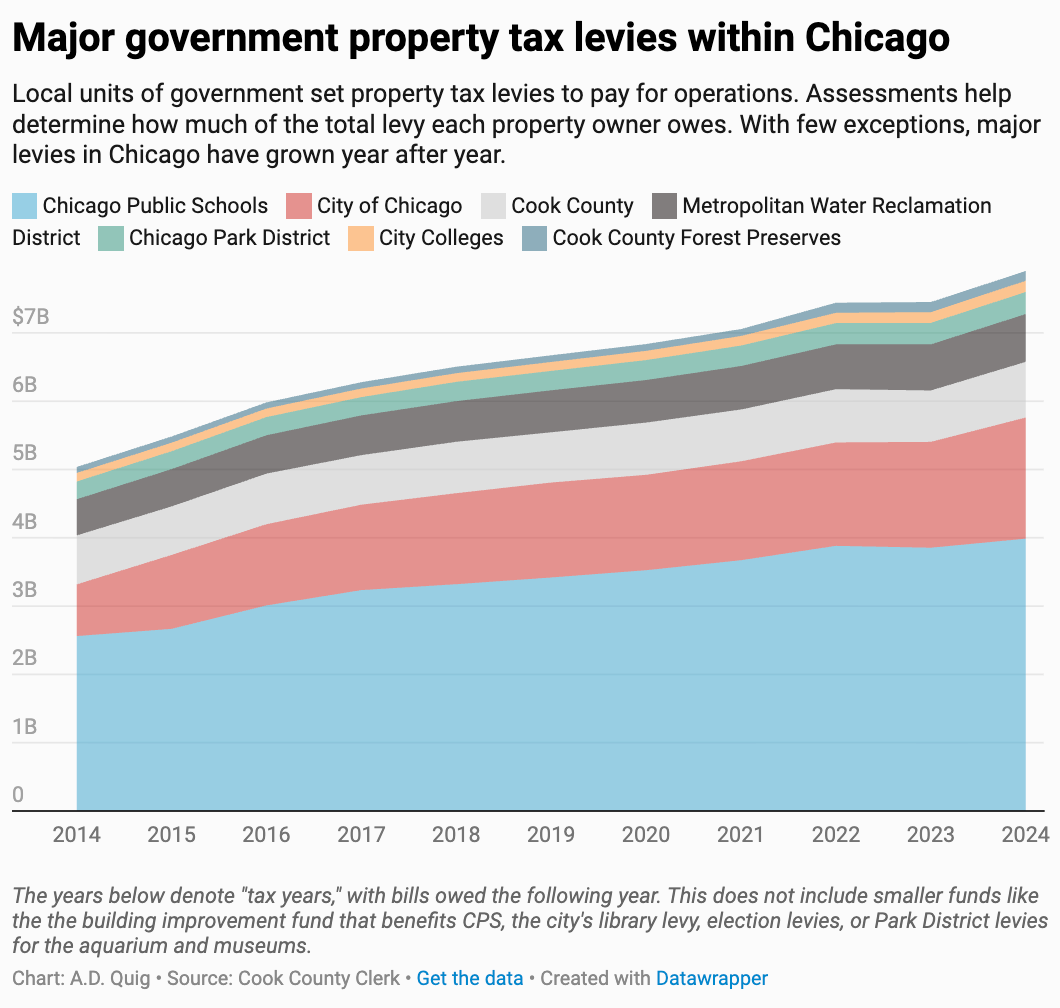

Chicago Tribune reporter A.D. Quig wrote a great story about those growing property tax bills, and readers took note of the graphic below, showing the extent to which the city’s growing property tax burden is the result of Chicago Public Schools. The CPS property tax levy grew to $3.99 billion in 2024 from $2.56 billion in 2014.

A fantastic new report from the Civic Federation and the Mansueto Institute for Urban Innovation at the University of Chicago shows how CPS is running an end-around to grow property tax levies far beyond what state law is supposed to allow—with TIFs playing a key role.

Here are the toplines:

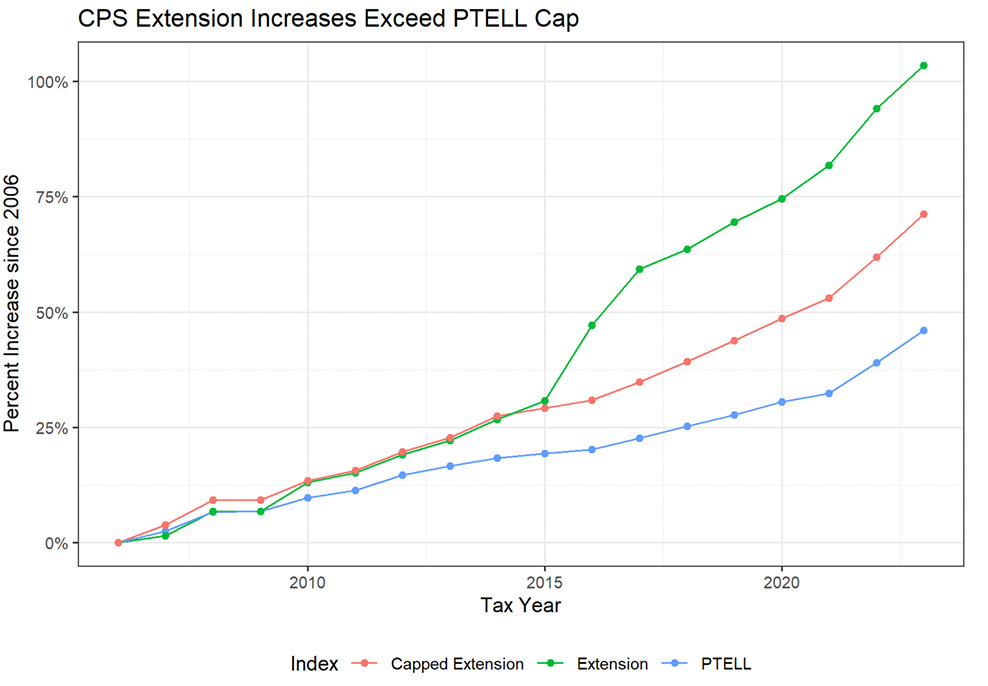

CPS is subject to a statewide property tax cap called the Property Tax Extension Limitation Law, or PTELL, which is supposed to limit annual growth in its property tax levy to the lesser of inflation or 5%.

If CPS wants to hike property taxes beyond that limit, the district is required to ask voters for permission via referendum.

From 2006-2023, the CPS property tax levy should have grown by around 50% under PTELL. Instead, CPS grew its property tax levy by more than 100% over that time period. But Chicagoans never got to vote.

Why? Due to a loophole in PTELL, the hundreds of millions of dollars in property tax revenue sent to CPS via TIF surpluses every year don’t count toward the property tax cap. CPS also levies a special property tax charge to fund pensions that doesn’t count toward PTELL.

In short, CPS maxes out its PTELL-capped levy every year, and then collects TIF surplus money and other “uncapped” funds on top of that. The result: Runaway property tax increases with voters having no say.

The blue line below shows the growth in the CPS property tax levy if the district had fully obeyed the property tax cap. The green line shows what actually happened.

If CPS had not exploited the loopholes in PTELL, the typical homeowner in Chicago would have saved more than $300 on their property tax bill in 2023 alone, according to the report.

And if every local government into which Chicagoans pay property taxes had been subject to PTELL without loopholes from 2007-2023, the numbers are even more stunning. Here’s a simple breakdown.

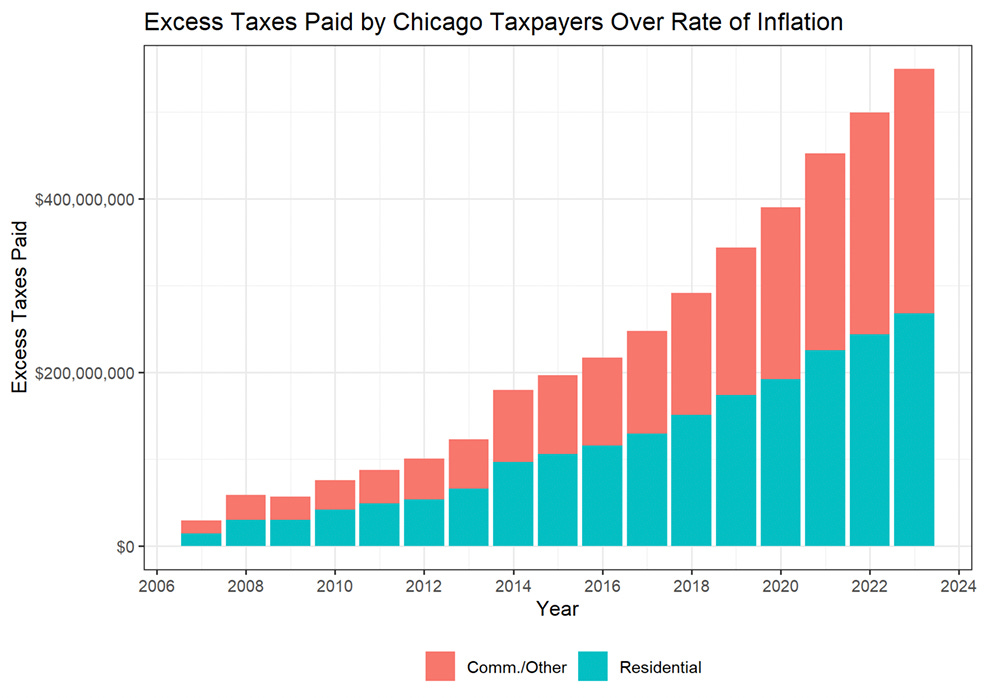

Chicago taxpayers would have saved almost $4 billion on their property taxes if local governments were actually restrained by the property tax cap from 2007-2023: $2 billion in savings for residential properties and $2 billion for commercial properties. In 2023 alone, Chicagoans would have saved $550 million on their property taxes.

Fix the loopholes and sunset TIFs

If political leaders can abuse TIFs as an end-around for sensible limits on property tax growth, that means both TIFs and the state’s property tax caps are broken.

To fix this, state lawmakers should close the TIF loophole in PTELL. And City Council should allow current TIFs to sunset.3 To spur development in truly blighted areas, the city could use simple, shorter-term property tax abatements instead.

Stop the shell games, and let voters decide whether to hike property taxes beyond inflation.

In the news

I joined Jon Hansen and Brandon Pope on WGN Radio for the Mincing Rascals podcast to talk about the head tax, sidewalk delivery robots in Chicago, former House Speaker Michael Madigan’s prison sentence and more. Listen here.4

Earlier this year, the Chicago Policy Center joined the Better Government Association and the Civic Federation to screen Drop Dead City, a vital documentary on New York City’s brush with bankruptcy in 1975. The film is now available to stream on Amazon.

My “green light” recommendation: I cannot recommend more highly “Songs of Good Cheer,” the annual holiday caroling tradition helmed by Mary Schmich and Eric Zorn, which is staged at the Old Town School of Folk Music and entering its 27th year. Tickets to the final show of the season this afternoon are sold out. Set a calendar reminder for 2026 if you missed it.

Yodeling to “The Friendly Beasts,” a Christmas song that originated in 12th century France.

This is the administration’s estimate for a newly floated $33 per employee per month head tax applied to businesses with over 500 employees. It would make Chicago a severe outlier among peer cities.

Or 35 years, if City Council and the mayor renew the TIF.

If they are not renewed, 95 current TIFs are set to expire by 2036, an 88% decline.

On a related note, my clip of Mayor Brandon Johnson struggling to cite just one other big city pursuing a head tax earned 1.5 million views. Kudos to Mary Ann Ahern for this great question.