Remembering Chicago’s greatest Thanksgiving

Lessons from a manmade catastrophe.

One of Chicago’s best winter traditions begins next week, when Andrew Bird turns Fourth Presbyterian Church into a glowing sanctuary of violin loops for his annual Gezelligheid concerts.

Most people who shuffle into the pews, wrapped in scarves and thawing their hands, have no idea they’re sitting inside a monument to one of the city’s oldest, hardest-won forms of resilience.

It’s a history worth recalling.

Especially now, as Chicago grapples with the heavy weight of poor decisions past and present.

The story begins just before Thanksgiving, 154 years ago.

A short-lived celebration

On the morning of Oct. 8, 1871, nearly a thousand Chicagoans crowded into Fourth Presbyterian Church at Wabash and Washington for what was meant to be a milestone.

It was the inaugural Sunday service after the merger of Westminster Presbyterian and North Presbyterian, held in a sanctuary that had just undergone months of renovations to unite the two congregations under one roof.

The pews were filled with families, clerks, merchants, teachers, and civic leaders. And although no attendance roll survives, the church’s early life had been shaped by some of Chicago’s most influential figures, most notably Cyrus McCormick.

The sanctuary was bright with autumn light and alive with the feeling of a fresh beginning. The congregation was finally whole.

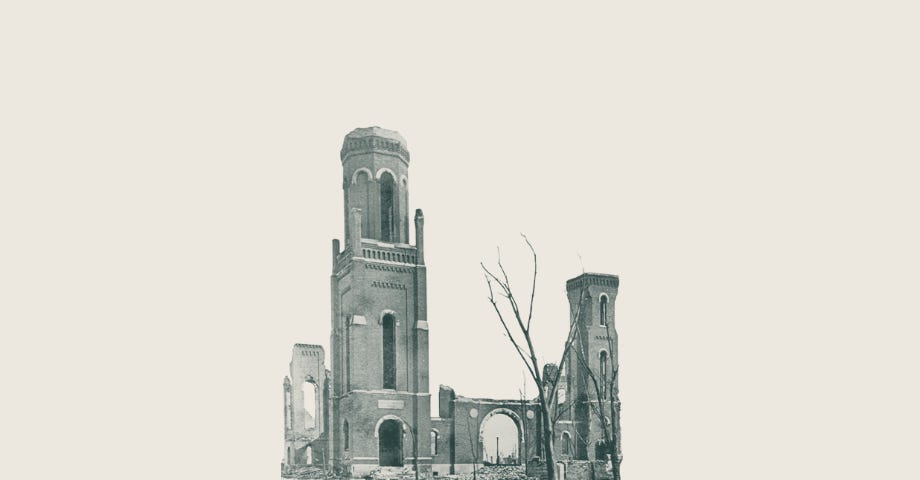

But by nightfall, the church would be gone. The homes of 125 of its 130 founding members burned with it.

They were engulfed by the flames of the Great Chicago Fire.

Giving thanks

In the months after the fire, the uprooted congregation met wherever they could—other churches, rented halls, any room that hadn’t burned—under the guidance of the controversial but widely admired David Swing.1

Where other pastors thundered that the fire was divine punishment for Chicago’s sins, Swing preached instead that a new Chicago would rise from the ashes, and that grace could be found not in judgment but in the extraordinary human generosity that followed.

No written record survives of Swing’s Thanksgiving sermon that year. But the Chicago Tribune captured the spirit of his congregation in a three-paragraph editorial, published the day before Thanksgiving in 1871.

It remains one of the most striking written pieces in Chicago history.

“The return of the thanksgiving festival has more than ordinary significance to the people of Chicago. Never in the history of civilized peoples has such a calamity fallen so suddenly upon so large a number of civilized persons, as that which destroyed the heart of this city in October last. Though one hundred thousand persons were rendered homeless in a few hours; though a majority of these endured suffering and privations; though many were bereft of all they had, and have been indebted to others for food and shelter, though hundreds of households mourn the loss of dear faces, which were last seen in that direful conflagration, nevertheless, no people have such cause for special thanksgiving as the stricken people of this great city.”

“In the Chicago fire it has been demonstrated that human sympathies and human love are limited to no geographical lines, bounded by no seas, circumscribed by no degrees of latitude, but are as broad as Christendom. The world is better for this calamity. This universal exhibition of brotherhood has been cheaply bought, even with the destruction of Chicago; for it has been shown that every blow that falls upon any considerable number of the human family is felt by all other men; and that, despite the separation of nations and the diversity of language, mankind is, after all, but one family, rejoicing in each other’s prosperity, and sharing the sorrows of the afflicted. There is no one who does not think better of his race, or who does not find his own bosom softened in admiration of this grand outpouring of charity and human love.”

“The people of Chicago have suffered what no pen can record. Individual loss has been general, and, in many cases, overwhelming. But, though sixty days have not elapsed since our treasures vanished in smoke, there is not a heart that does not revive in the work of restoration already far advanced. We have lost much, but much is still left us. In the light of the past, avoiding its errors and guided by its experience, we are rebuilding the burned city, and hastening the growth of the New Chicago, which shall exceed in durability and strength, in wealth, population, and power, anything that even the most sanguine had expected. For all this we have special cause for thanksgiving. The fire swept away our accumulated gains, but it did not smite down our energy. It left us our commerce; it did not destroy the agencies by which the vast trade of the city was conducted. It burned down our stores and our warehouses, but it did not destroy the business that was done in them. When we count up the sales of goods, the receipts and shipments, the labor performed and the productions resumed since the fire, and find that they have compared favorably with any corresponding period in our history, we should be ingrates indeed if from our hearts we did not give thanks for such an outcome from the great calamity.”

Today, many Chicagoans are rightly disturbed and discouraged by the city’s poor results. But they would be wise to heed the optimism and resolve of the Chicagoans who survived a catastrophe of biblical proportions and yet—not even two months later—gave thanks for the fire, and for the work ahead.

Those claiming Chicago’s conflagration was due to devilish sins were wrong. “Our city has been punished for its sin, they will say,” wrote the Chicago Evening Post about such figures, “forgetting that the punishment is only upon our terrible iniquity of shingle-roofs and balloon frames.”

Similarly, Chicago’s poor governance today did not come from the heavens. Our problems are manmade. And that is a blessing. Because so, too, are the solutions.2

In the news

CTU AUDITS

Last week I filled you in on the Chicago Teachers Union audits scandal, with a U.S. House committee formally requesting audits that members have been demanding for the last five years. Since then, a CTU lawyer responded to Congress saying the union would “fully answer any legitimate questions.”3 Local media ran several stories with more claims of cooperation. But we were first to publish leaked screenshots showing that behind closed doors, union leadership was saying the exact opposite. CTU VP Jackson Potter told members asking for the audits that publishing them would be “appeasement to a bully.” I joined Tahman Bradley on WGN to discuss the case. The Chicago Tribune editorial board also called on the CTU to release its audits.

BANKRUPTCY AND BAILOUTS

The Chicago Policy Center’s work was cited in a new edition of Statecraft, “Should the feds bail out Chicago?” In the piece, Institute for Progress Editorial Director Santi Ruiz interviews Yale Prof. David Schleicher on his great book, “In a Bad State: Responding to State and Local Budget Crises.” Recommended.

MINCING RASCALS

I joined John Williams, Eric Zorn, and Jon Hansen on the Mincing Rascals podcast to discuss 10 years since the release of the Laquan McDonald tape, two scandals at Chicago Public Schools, and more.

Their next permanent home wouldn’t come until 1874, when they built a new church at Rush and Superior. Another move followed four decades later, in 1914, to their now-iconic Gothic Revival building on North Michigan Avenue—the one where Bird performs today.

In 2023, I gave a speech on this subject to the Ethical Humanist Society of Chicago. You can watch it here.

The same lawyer, Michael Bromwich, also served as Kim Foxx’s personal attorney during the special-prosecutor probe into her office’s handling of the Jussie Smollett case.