Everything you need to know about the Chicago Teachers Union's audits scandal

Local teachers' fight for transparency has finally reached Congress.

Chicago’s largest political spender is now under federal scrutiny.

On Nov. 20, the U.S. House Committee on Education and the Workforce sent a formal demand letter to Chicago Teachers Union President Stacy Davis Gates.

The committee wants the last five years of CTU audits—the same audits CTU has refused to release to its own teachers since 2020. The letter cites my colleague Mailee Smith’s reporting on this issue, as well as my own.

This is the first time in the union’s modern history that elected officials have stepped into what CTU leadership has insisted is an “internal matter.”

It’s not an internal matter anymore.

Teachers are fighting their own leadership for the right to know where their money went. And that fight has finally reached Congress.

At the same time, this scandal is often misunderstood. And a prime example of why criticism of CTU leadership should not be taken as criticism of rank-and-file educators.

Let’s get into it.

The rules CTU is violating

Let’s start with what CTU’s own governing documents require.

The union’s Constitution and Bylaws mandate an annual independent audit of CTU’s finances that is published for members.1

And CTU followed those rules—until it didn’t. The last audit ever shown to members was posted Sept. 9, 2020. That’s 1,901 days ago.

After that, the reports stopped. And the union has never given a coherent explanation for why.

Why the audits suddenly disappeared

The silence coincided with a dramatic shift in CTU’s finances.

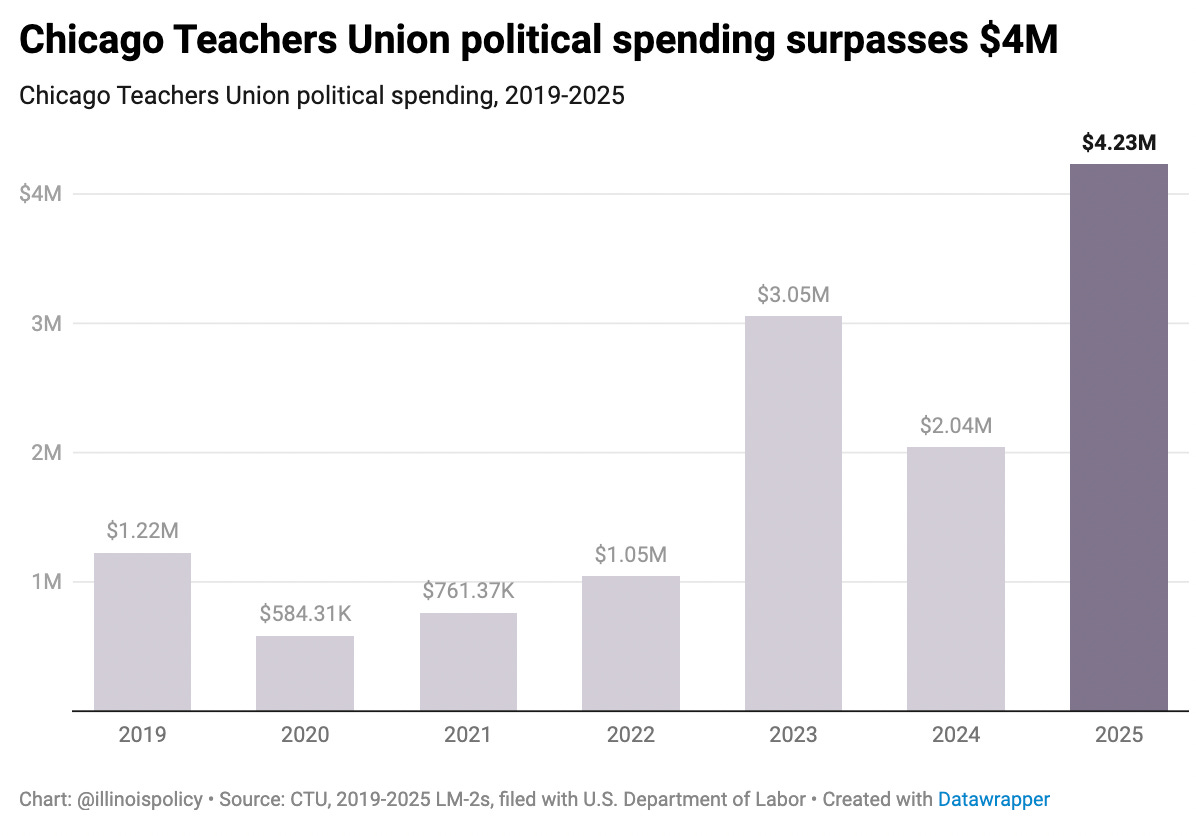

First, political spending increased sharply, reaching record highs as CTU transformed into the state’s most aggressive political machine.

At the same time, spending on services for members declined. The union now spends just 18 cents of every dollar on actually representing teachers in the workplace.

Leadership also hiked member dues. And shortly after the union stopped publishing annual audits, rumors began to circulate that as much as $8 million had gone missing from CTU coffers.

In fact, the talk became so widespread that Brandon Johnson—then a CTU lobbyist and Cook County commissioner—addressed it directly in 2022.

As shown in a leaked video published exclusively by The Last Ward, Johnson denied allegations of missing funds while campaigning on behalf of Stacy Davis Gates in the union’s internal elections.

“You think it’s worth me hiding $8 million from thousands of members? To put my own family at risk for that? I wouldn’t do that,” Johnson said.

“And don’t think if I did do something like that, [that] folks wouldn’t come to try to figure out how to take me down.”

Members were concerned, to say the least.

Teachers ask questions, then get smeared

Rank-and-file educators began making formal requests for the audits.

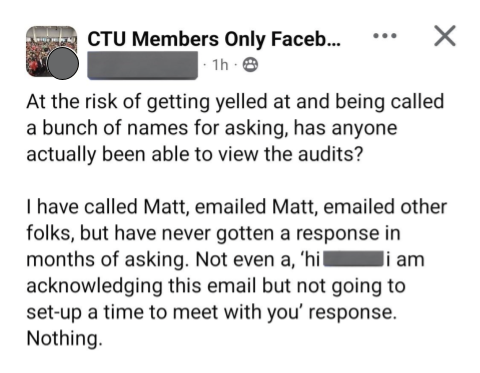

At first, they were ignored. Here’s what one educator posted about their experience with CTU Chief of Staff Matt Luskin, for example.

Then, the union started making false promises. Kurt Hilgendorf, special assistant to Stacy Davis Gates and head of union finances, posted a statement about the audits in a private Facebook group. He blamed “complex litigation” as the reason for the delays, but assured members they could see the audits soon.

“Audits have been procured,” Hilgendorf wrote. “They’re just not quite done yet … [the audits] should be done in the next several weeks and can be shared at that time.”

That was in 2023. The audits never came.

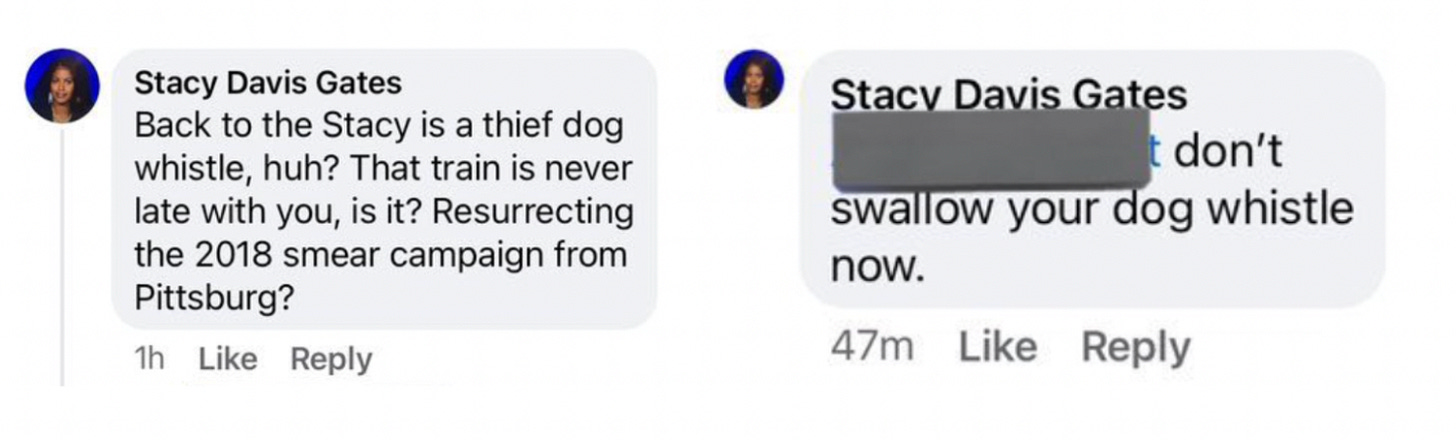

Finally, members requesting audits were personally attacked, with Gates calling their concerns a racist “dog whistle.”

Members were stuck: bullied and silenced by their own union president.

Members turn to the law

With no internal path left, four members turned to the Liberty Justice Center, which filed a lawsuit on their behalf in Cook County, seeking to force CTU to follow its own financial transparency rules.

“CTU members deserve to know where their money is going,” said plaintiff Phillip Weiss, who has been a CTU member since 1998.

“This lawsuit isn’t just about us—it’s about the more than 25,000 educators across Chicago who rely on the union to uphold its commitments.”

The response from CTU leadership was revealing: They tried to intimidate the members who filed the lawsuit. And they moved to dismiss the case outright. A Cook County judge rejected that request, allowing the lawsuit to continue.

The union then requested summary judgement in the case. Plaintiffs are awaiting the judge’s ruling on that request.

Encouragement from City Council

Mayor Johnson has not commented on the audit matter at all, in public. One alderman, however, has spoken up.

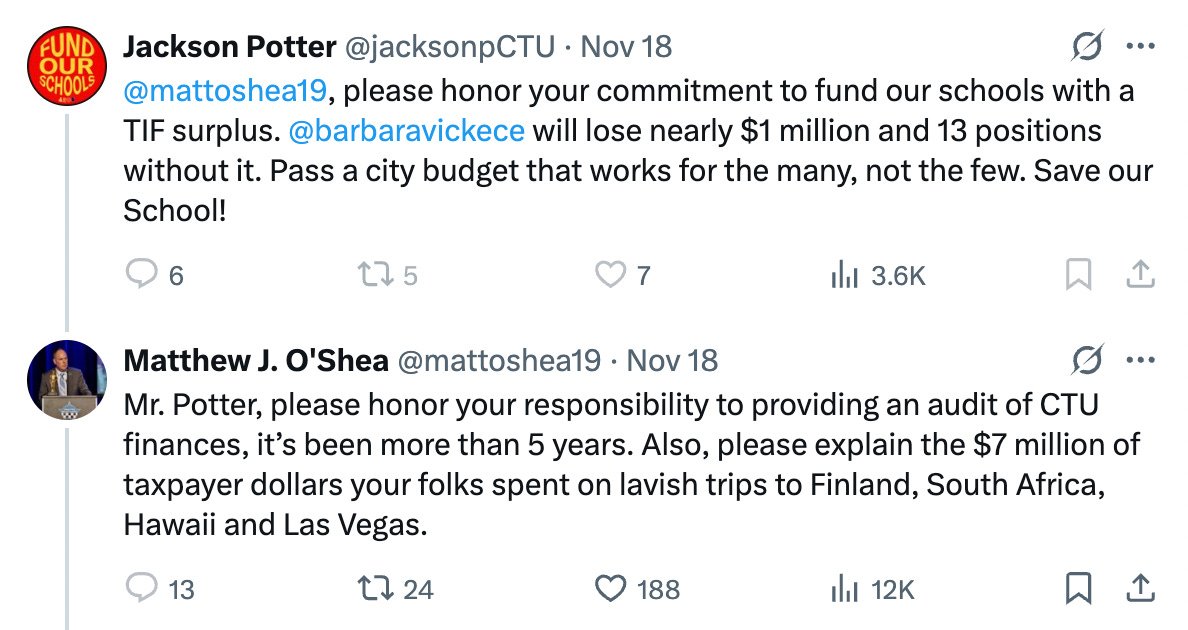

Ald. Matt O’Shea publicly confronted CTU Vice President Jackson Potter on X last week, calling on Potter to “honor your responsibility to [provide] an audit of CTU finances, it’s been more than 5 years.”

It was the first time any sitting alderman challenged CTU leadership about the audits, on behalf of teachers.

Congress steps in

On Nov. 20, the U.S. House Committee on Education and the Workforce formally demanded CTU produce all unabridged audited financial reports for FY 2019-2024.

The deadline: Dec. 8.

This letter is not a subpoena. CTU can choose to ignore it. But refusing to comply could cause problems for the union.

Here’s why.

When CTU files its annual Form LM-2 with the U.S. Department of Labor, it must disclose whether it completed an independent audit. Each year, the union answers “yes.” Stacy Davis Gates then signs the filing, attesting under penalty of perjury that the information is “true, correct and complete.”

That certification presumes the underlying audits exist and are accurate.2

But if CTU submitted LM-2 filings based on audits that do not exist—or on financial information contradicted by the audits—federal agencies could open civil or criminal investigations. The Department of Labor handles civil enforcement under the Labor-Management Reporting and Disclosure Act, while the Department of Justice brings criminal cases.

And there’s more.

If CTU stonewalls Congress, or if the audits reveal deeper problems, lawmakers suggest in the letter that the scandal could trigger reforms to federal labor law. That could include tightening financial-disclosure rules for government-sector unions, strengthening audit requirements, or restricting how unions spend member dues on politics.

In short: CTU’s refusal to follow its own bylaws could become the catalyst for national reform.

What’s next?

In the coming months (possibly weeks, or even days) a Cook County judge will rule on the union’s request for summary judgment in the members’ lawsuit. The court may ultimately force CTU to produce the audits.

But the courtroom is no longer CTU’s only problem.

The House committee’s Dec. 8 deadline creates a parallel track with higher stakes. Even if CTU slow-walks the case in Cook County, Congress can escalate its inquiry at any time—and federal agencies don’t need Congress’s permission to investigate potential violations of federal law.

Whatever happens next, this much is clear: CTU leadership turned a routine financial disclosure into a years-long scandal by refusing to follow their own rules.

Teachers did not create this mess.

They are the ones trying to clean it up.

UPDATE (12/1): A CTU lawyer responded to Congress saying the union would “fully answer any legitimate questions.”3 Local media then ran several stories with more claims of cooperation. But we were first to publish leaked screenshots showing that behind closed doors, union leadership was saying the exact opposite. CTU VP Jackson Potter told members asking for the audits that publishing them would be “appeasement to a bully.” I joined Tahman Bradley on WGN to discuss the case. The Chicago Tribune editorial board also called on the CTU to release its audits.

In the news

On Friday evening, I joined Paris Schutz on Fox32 Chicago to discuss the audits scandal. You can watch the segment here. I also joined the Real Clear Politics Podcast to discuss news of the largest residential property tax increase in Chicago in 30 years.

The Chicago Policy Center’s work comparing head taxes in other big cities was cited by the Wall Street Journal editorial board in their story on the tax’s defeat in City Council, A Tax Revolt in . . . Chicago?

Mr. Johnson’s idea is to levy a tax of $21 per employee on businesses with more than 100 workers. This would punish companies that are doing Chicago a favor by staying in downtown offices despite the city’s dysfunctions, rather than fleeing elsewhere. Only three other big cities have a head tax, according to the Chicago Policy Center, and Mr. Johnson’s plan has a far higher rate than the ones levied by Denver, San Jose and San Diego.

The pushback should be a warning for City Hall, which prefers to bet Chicago’s future on more taxes and high-interest loans. It’s a toxic cycle: Property taxes on Chicago homeowners last year went up some 16.7%, or $469 million, in part due to declining commercial property values downtown. “This head tax is only going to make things worse,” Alderman Brendan Reilly said. “The shift is being put on the homeowners, because commercial properties are paying less, because they’re valued less, because they’re empty. That’s why.”

Yet Mr. Johnson is doubling down. “The corporate tax is in this budget. It will stay in this budget,” he said. Asked in a press conference whether piling on more taxes would hurt the downtown economy, the Mayor blamed the vacancy rate on the lingering effects of Covid: “There is no correlation between taxation and the success, if you will, of corporations.”

Is it too taxing on the mayor to understand Econ 101?

And I spoke to John McCormack at The Dispatch for his story on Operation Midway Blitz,4 which was published before Border Patrol Commander Gregory Bovino left Chicago:

“Tensions are extremely high, and it’s a very unhealthy information environment,” Austin Berg, executive director at the Chicago Policy Center at the Illinois Policy Institute, told The Dispatch.

“That unhealthy information environment, I think, has been worsened by, in some instances, the federal government, in some instances local media, in some instances local officials.”

The biggest problem with information from the federal government, Berg said, was its unreliability. For example, Berg pointed to a recent video of ICE agents detaining a U.S. citizen named Debbie Brockman. DHS said she was detained for throwing objects at ICE agents—which Brockman and her attorneys deny—but she was released without charges.

“So what does that fact pattern leave people with? They don’t know what’s true,” Berg said.

My “green light” recommendation: Chicago band Sharp Pins’ new album, Balloon Balloon Balloon.

Specifically, the union’s financial secretary is required to “furnish an audited report of the Union which shall be printed in the Union’s publication.” And the Board of Trustees is required to “procure each year, a reliable and adequate audit of the finances of the Union for the preceding fiscal year ending June 30, and to deliver a copy of said audit to other major officers and to announce to the membership of the Union that said report may be inspected in the Union office by any member.”

Note that while Hilgendorf told members in 2023 that the audits for three previous years were “not quite done yet,” the union was telling the Department of Labor a different story. CTU has consistently answered “yes” to the following question on their annual Form LM-2, which is filed with the Department of Labor and signed by Gates: “During the reporting period did the labor organization have an audit or review of its books and records by an outside accountant or by a parent body auditor/representative?”

The same lawyer, Michael Bromwich, also served as Kim Foxx’s personal attorney during the special-prosecutor probe into her office’s handling of the Jussie Smollett case.

Excellent reporting as usual. I look forward to learning about the audit.

Just completed my paid subscription (before completing the story). The reporting in therein utterly validates that decision.

This episode is all about power. The membership of CTU is just the cash register to those in its leadership. Their dues fuel the political agenda of these so-called leaders.