Chicago is investigating how residents learned of a meeting to hike their property taxes

It's story that reads like The Onion. But there’s a deeper issue here.

Chicago Board of Education President Sean Harden called a special meeting over the Christmas holiday. He had one objective: Quietly pass a $25 million property tax hike.

One might understand why Harden wanted to keep it under wraps.

Weeks earlier, Chicago homeowners saw the largest residential property tax hike in at least 30 years. And the man who appointed Harden to his post, Mayor Brandon Johnson, just spent months talking about how he was refusing to hike property taxes as part of the city budget.

Best not to mix messages.

But Harden’s plan hit a snag. Fox 32 Chicago political reporter Paris Schutz published news of the meeting before the school board posted a public notice of its own.

And now Harden—with Johnson’s imprimatur—is spending taxpayer money on a law firm to conduct an investigation into how news of the meeting leaked to a journalist.1

The headline is Onion-esque: Mayor uses property taxes to investigate how residents learned of higher property taxes.

But there’s a deeper lesson here.

The real problem

Here is one maxim of Chicago’s political culture: The more dramatic the story, the less likely residents will grasp its most important lessons. Call it Gift Room Syndrome.2 And it certainly applies here.

The big scandal isn’t the board voting to hike property taxes by $25 million, though that is worth noting. (You can find the roll call below.)

MEMBERS VOTING NO (5): Carlos Rivas; Ellen Rosenfeld; Angel Gutierrez; Che “Rhymefest” Smith; Therese Boyle. MEMBERS VOTING YES (15): Jennifer Custer; Jessica Biggs; Yesenia Lopez; Ed Bannon; Anusha Thotakura; Ebony DeBerry; Cydney Wallace; Karen Zaccor; Olga Bautista; Emma Lozano; Michilla Blaise; Norma Rios-Sierra; Angel Velez; Jitu Brown; Debby Pope. Don’t know your board member? Click here.

And while it is absurd, of course, the big scandal isn’t even the investigation into how taxpayers learned about the meeting.

The biggest scandal here is that the school board is subverting democracy.

Specifically, Chicagoans should be seeing a referendum vote on an extra $550 million increase in property tax collections that will flow to Chicago Public Schools this year, above what’s allowed under the state’s property tax cap.

But Chicagoans will not get that vote.

How CPS is ignoring voters

Illinois has a property-tax cap in state law. That cap limits how much local school boards can hike property taxes in a given year. Go above the cap, and the board must ask voters for permission via referendum on the ballot.

Every year, the Chicago school board votes to hike property taxes up to the maximum allowed without triggering a referendum. And this time was no different, as CPS Chief Financial Officer Wally Stock explained at the Dec. 29 board meeting.

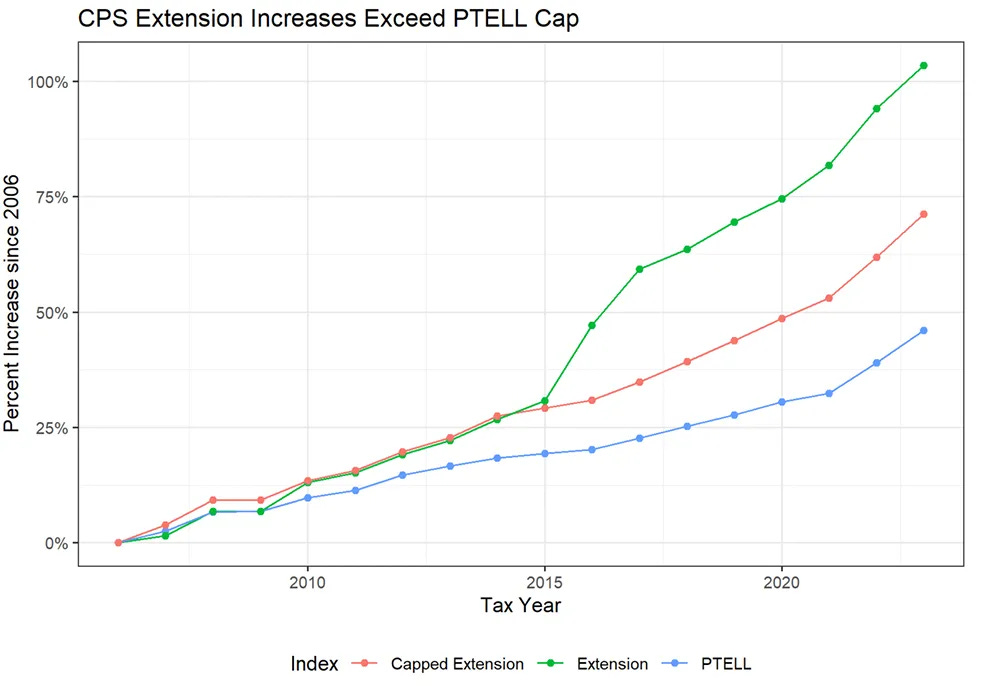

But if those board votes were the only source of CPS property tax growth, Chicagoans should have expected property taxes for schools to increase by around 50% from 2006-2023.

Instead, CPS property taxes grew by more than 100% over that time.

And Chicagoans never got to vote on it.

The main reason for growth in property taxes exceeding the state cap is the TIF loophole. In short, the city squirrels away money into Tax Increment Financing (TIF) districts, but then sweeps those TIF funds into CPS and other local governments. And the TIF sweeps don’t count toward the property tax cap. This is why TIFs are best understood not as an economic development tool, but as Chicago’s secret property tax hikes.

Because of that loophole, $550 million in extra property tax revenue above the cap will flow into CPS this year—without a vote of the people.

That’s the real scandal.

Voting on higher taxes, debt

Getting voter sign-off on new borrowing or property tax hikes beyond a certain limit is a common practice in big cities across the country.

But not in Chicago.

As the Wall Street Journal editorial board recently highlighted:

Nearly every other U.S. big city requires voter approval for increasing general obligation debt. In Los Angeles, Houston, Phoenix, San Antonio, San Diego and others, voters are required to approve general obligation bonds, according to the Chicago Policy Center. New York and Chicago don’t require voter approval.

The reason for requiring voter approval is simple: accountability. It forces public officials to show their work.3

In the news

Last week’s edition of The Last Ward on why you can’t start a Chicago-style hot dog cart in Chicago got a lot of attention. In short: There is strong, bipartisan support for #hotdogabundance. Keep an eye out for another piece on this topic in a major national outlet this week.

I joined The Mincing Rascals podcast on WGN last week to discuss the ICE shooting in Minneapolis, Nicolás Maduro’s capture, and the Chicago mayoral race. You can listen wherever you get your podcasts (including, for the first time, YouTube).

My “green light” recommendation: the Chicago Printmakers Collaborative in Lincoln Square, which is home to this incredible sign.

Also included in the investigation: how the names of job candidates to become Chicago Public Schools’ next superintendent leaked to journalists.

The infamous gift room scandal was not about Brandon Johnson hoarding illicit gifts for his personal benefit. Much more concerning was the inspector general’s report revealing public officials’ blatant disregard for Chicago’s Government Ethics Ordinance via a decades-long “unwritten agreement” between the Board of Ethics and the mayor’s office, as well as the city’s corporation counsel actively interfering with the investigation into the gift room—clearly working on behalf of the mayor’s interests rather than the city’s. You can read more on the lessons of the gift room scandal here.

Voters in major cities often agree with leaders’ arguments for new taxes and debt. For example, there was $16 billion in borrowing on the ballot for state and local governments in 2025, according to Bloomberg, and $12 billion passed. But sometimes, residents don’t go along. Johnson’s Bring Chicago Home referendum is one example. Had the mayor and his allies been more forthcoming about where that new money would be spent, it’s possible voters would have narrowly approved. But Johnson chose not to do that. Voters defeated the measure, with 52% voting no.