5 steps Chicago’s next mayor can take to fix city finances

Here’s how to tell if a candidate is serious about putting the city on more stable ground.

As predicted, cracks are already forming in the budget passed by Chicago City Council late last year.

Crain’s Chicago Business reported last week that Chicago municipal bonds have moved sharply against the broader market.

Chicago has “gone in completely the opposite direction of the market as a whole” since the start of 2026, according to University of Chicago municipal finance expert Justin Marlowe. Investors are demanding higher returns to hold Chicago debt even as borrowing costs ease elsewhere.1

Unlike many other big cities, Chicago’s greatest challenge has nothing to do with its land, the environment, talent, or basic infrastructure.

Chicago’s greatest challenge is its horrific financial situation, which came about due to decades of poor decisions.

Here’s the good news: that is a manmade problem. The solutions are manmade, too.

So how can the current mayor, or the next one, ensure the city starts making better decisions?2

Chicago’s financial freefall

Chicagoans should be wary of politicians who talk a good game on financial stability, but are unwilling to tackle the uncomfortable conversations needed to get there.

That starts with honesty about where the city stands today. Here are the lowlights:

Chicago holds more pension debt as a city than 44 of 50 U.S. states ($53 billion)

Seven of the 10 worst-funded pensions in the nation are in Chicago.

More than 40% of all city spending goes toward debt and pensions. That’s the highest share of any big-city budget dedicated to fixed costs by far, according to S&P Global.

Chicago commercial property owners shoulder the highest property taxes in the nation. But more than 80% of the city’s property tax levy goes straight to pension costs—not services.

Chicago Public Schools is the largest municipal issuer of junk bonds in the nation.

While growing the city’s economy is the best way to solve these problems—see the Chicago Abundance Agenda for ideas—that is simply not enough on its own. And unlocking more growth itself requires reforms to reduce Chicago’s government debt, which is currently repelling business investment.

Below are five things Chicago Mayor Brandon Johnson could do to right the ship.

But based on his performance thus far, Johnson is unlikely to pursue any of these.

So candidates for his job in 2027 should take note.

1. Stop digging: No more pension sweeteners

The first step to getting out of a hole is to stop digging. But Chicago refuses to stop.

Chicago police and fire already have among the worst-funded pensions systems in the country. But new pension sweeteners for Chicago police and fire passed the Illinois General Assembly with barely a peep from the mayor’s office last year—adding $11 billion in new liabilities and dropping the funds to just 18% funded after the governor’s signature.

Chicago CFO Jill Jaworski wrote to the governor’s team that the bill would make Chicago’s police and fire pension funds “technically insolvent.” But that was after it had already passed the General Assembly. The governor signed the bill anyway.

Kudos to Illinois Comptroller Susana Mendoza for being the only prominent public official to speak out against these extraordinarily irresponsible sweeteners.

Every candidate for public office in Chicago should commit to a simple promise: no more pension sweeteners.

2. Advocate for allowing Chapter 9 bankruptcy

Chicago is the only big city in the country that cannot restructure its debt in federal bankruptcy court.

Without the option of Chapter 9 bankruptcy, city government is increasingly becoming less of a service provider and more of a collection agency that transfers wealth from the young to the old—until the city reaches a breaking point.

Note that the mayor doesn’t need to argue for entering bankruptcy. Simply having the tool on the table forces honest conversations with government-worker unions and other stakeholders. It could even help with renegotiating the city’s notorious parking meter deal.

Allowing the city to enter Chapter 9 requires a change in state law. The mayor will need to advocate for it. But the debt crisis unfolding in nearby Harvey, Illinois, offers a rare opportunity for Chicago leaders to proactively shape that legislation in Springfield.

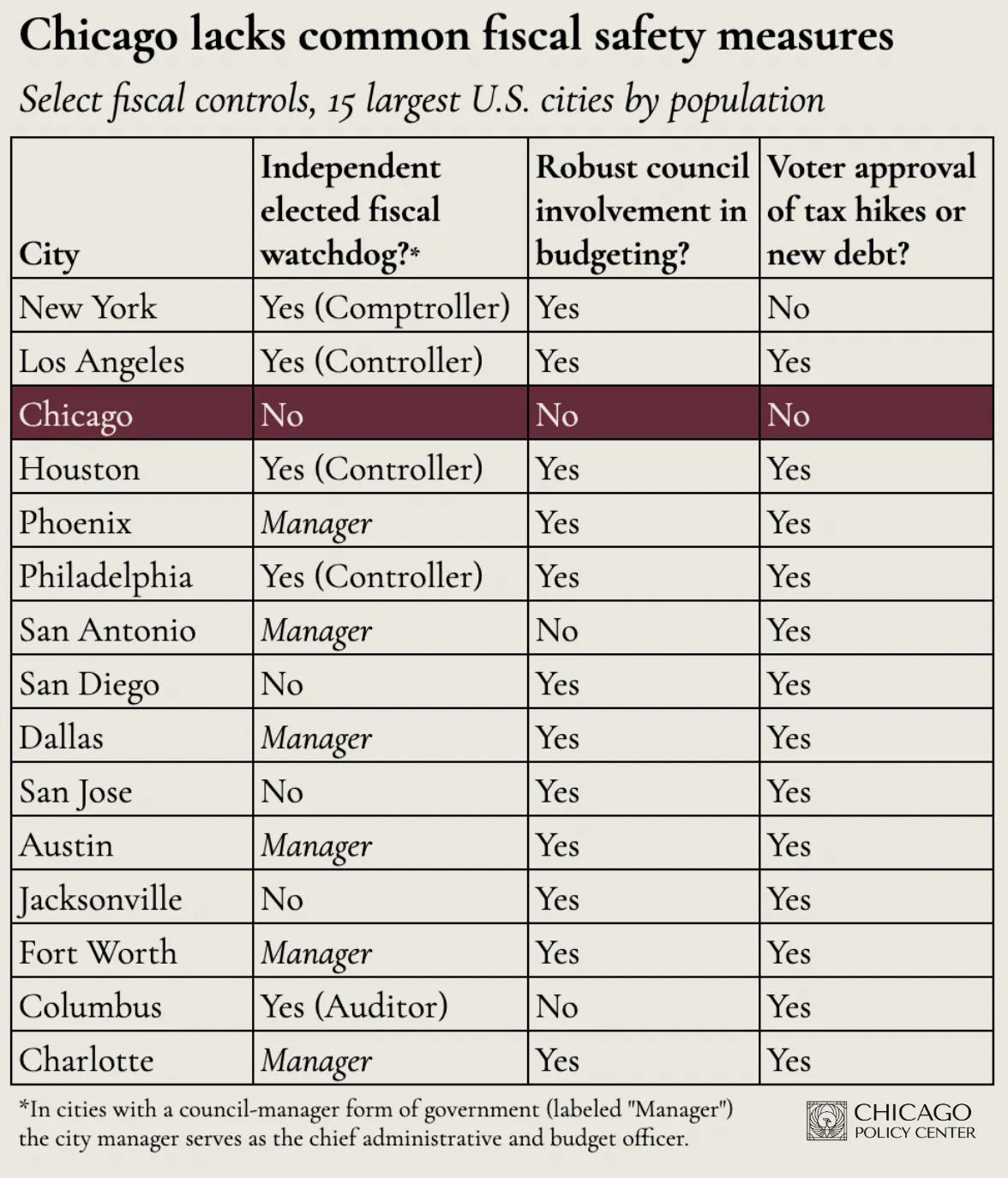

3. Improve financial oversight

As the most recent budget fight illustrated, Chicago is not equipped to implement structural changes in its budget, make good budgeting decisions, or even independently analyze the numbers outside of the mayor’s office.

The mayor should advocate for:

Creating an independent budget office a la New York City.

Filling the legally required position of city administrator, which could help implement the budget and lead a zero-base budgeting process.

Changing the responsibilities of the elected city treasurer to be more like a CFO or comptroller, based on similar offices in New York, LA, and Houston.

All of these measures are common in other big cities.

Every large American city lays out these checks and balances in a voter-approved city charter. But not Chicago. Chicago is the only big city in the country without this governing document.

Chicago’s lack of a city administrator is one glaring example of why a charter is so necessary. Without a city constitution, Chicago mayors have been able to ignore filling this critical position since 1954, despite the Municipal Code of Chicago demanding the mayor “shall appoint” the officer, who must then be confirmed by City Council.

4. Empower voters to approve tax hikes and new debt

Chicago will likely need some form of new revenue to right the ship.

But lawmakers should have to make the case for tax hikes and new borrowing directly to voters, as they do in other big cities.3

In theory, Chicagoans already have far more authority over property tax hikes than it appears. But due to a TIF loophole that allows hundreds of millions of dollars in higher property tax collections for Chicago Public Schools without getting voter approval, voters rarely get a say on new taxes.

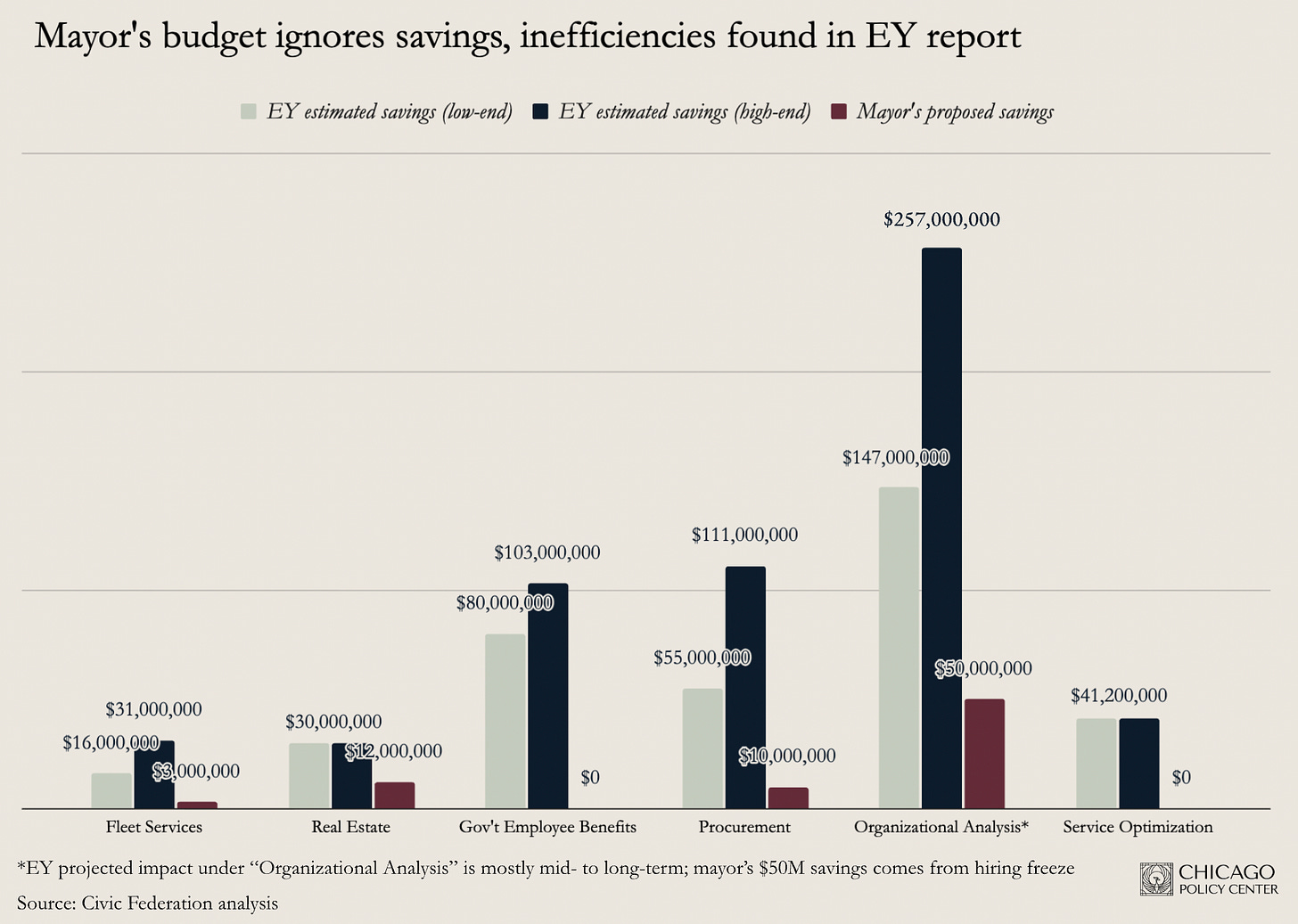

5. Follow the EY recommendations

The Johnson administration ignored $1 billion in structural savings identified in EY’s analysis of the city budget last year.

Chicago should implement 100% of the recommendations identified in the EY report.

In the meantime, the city should commission deeper analysis on each of the report’s subject areas, with findings presented to the City Council in open hearings.

Changing course

Chicago’s greatest challenge is not a lack of natural resources. Nor top-tier universities. Nor basic infrastructure.

It is the compounded effect of decades of poor financial decisions.

A better path is possible.

Mayoral candidates have a unique opportunity to chart that path, and win on a mandate to execute against it.

In the news

Last week I joined Chicago-bred entrepreneurs Ravin Gandhi and Al Goldstein on their podcast Forged in America for a wide-ranging conversation on the challenges facing Chicago and solutions that the next mayor should pursue (YouTube, Spotify, Apple Podcasts).

I also joined the Mincing Rascals podcast on WGN to discuss the Border Patrol shooting of Alex Pretti in Minneapolis, the race for Dick Durbin’s Senate seat, and more (YouTube, Spotify, Apple Podcasts).

My “green light” recommendation ahead of the Winter Olympics: White Rock (1977).

Reminder: I will be joining Paris Schutz and the Chicago Area Public Affairs Group at the Union League Club on Feb. 19 to discuss Illinois’ upcoming primary elections. Tickets here.

The piece also included an eerie quote from Municipal Market Analytics head Matt Fabian, who worried the city might turn to issuing pension-obligation bonds, a move that would almost certainly trigger credit downgrades. “There’s always the worry that the worse the situation gets, the more likely a really terrible idea will happen,” he said.

The hero image for this piece is a vintage, hand-painted sign displayed at the Chicago Printmakers Collaborative. Under no circumstance should candidates for public office seek inspiration from Mayor Richard J. Daley on fiscal policy.

Among the top 15 cities by population, 13 require voter approval to issue general obligation debt. New York and Chicago do not. But New York enjoys many more structural protections against bad borrowing, which Chicago lacks. Voters are often amenable to borrowing if they believe it’s going to a good cause. Per Bloomberg, there was $16B in borrowing on the ballot for state and local governments in 2025, and $12B passed.

Excellent post, and the Forged in America podcast is phenomenal!

I moved to Chicago suburbs from New York City where I lived in the aftermath of Giuliani administration during Bloomberg. Of course there are ways to improve public safety in Chicago - if NYC could do it, so could Chicago. But a lot has to change with the way voters process information and act on what they know, I believe.